Universal Chalcidoidea Database

Notes on families

Eupelmidae

Main diagnostic characters

1. Females and some males with mesopleuron large and undivided ( 100%, 25%), other males (75%) with mesopleuron obliquely divided and difficult to separate from pteromalids.

2. Gaster subsessile (100%)

3. Mid coxae inserted level with posterior margin of mesopleuron

(100%)

4. Prepectus normal, not enlarged (100%)

5. Male antenna with seven funicle segments and a single, very small annellus (100%)

Included taxa

The family currently includes 45 genera and 907 species placed in 3 subfamilies as follows: Calosotinae (8/144), Eupelminae (33/686), Neanastatinae (4/77).

|

|

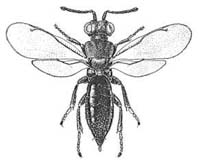

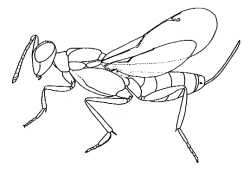

| Calostinae (Calosta sp.) |

Calostinae (Eusandalum barteli) |

Biology

The vast majority of species of Eupelmidae are parasitic and facultatively hyperparasitic on the immature stages of other insects, with hosts recorded in the orders Lepidoptera, Homoptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, Neuroptera and Orthoptera. Eupelmus urozonus and Eupelmus vesicularis are examples of species which may develop as primary ectoparasitoids or as ectoparasitoids of a great range of other primary parasitoids (Muesebeck & Dohanian, 1927; Morris, 1938; Askew, 1961). A small number of species are predators on the eggs or larvae of various insects, or on the eggs of spiders. A few are solitary, primary endoparasitoids of eggs of Lepidoptera, Orthoptera and Hemiptera. Most eupelmids are solitary, but some species are gregarious. Most are ectoparasitoids, including some that develop gregariously on dipterous pupae within puparia. A few species are solitary endoparasitoids of Coccoidea. Species of Calosotinae are mostly parasitic on the larvae and pupae of xylophagous beetles, though a common North American species, Calosota metallica, is a common primary or secondary parasitoid of a variety of other insects living in grass stems (Burks, 1979).

|

|

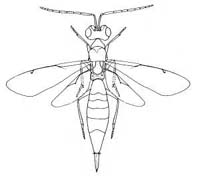

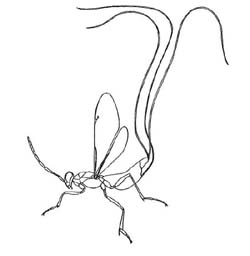

| Eupelminae (Anastatus bifasciatus) |

Eupelminae (Eupelmus sp.) |

The eupelmid egg is ellipsoidal and usually bears a stalk at one end. This stalk may be very long and is used by some species to attach the egg to a substrate or to the host's cuticle (Morris, 1938; Clancy, 1946; Askew, 1961). Other ectoparasitoid species simply place their egg in the vicinity of the host rather than on it; some species may cover the egg with a fibrous network (Phillips & Poos, 1921; Taylor, 1937). The first instar larva is elongate, 13-segmented, and usually has a bifurcate tail and a ventral row of spines (Clausen, 1927). In some species the spines may be missing from the abdominal segments, or there may be a pair of longer spines on each segment (Morris, 1938; Askew, 1961). The integument may be clothed in minute setae (Clancy, 1946). The final instar larva is robust, and may be very hairy (Morris, 1938). Overwintering is usually as a mature larva or pupa.

|

|

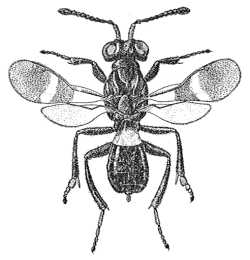

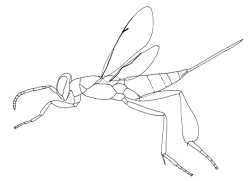

| Eupelminae (Eupelmus urozonus) |

Eupelminae (Eupelmus antipoda) |

The Eupelminae are of interest because of the unique adaptation of the sclerites and muscles of the mesothorax for jumping. This peculiar mechanism was first noticed by Walsh & Riley (1869) when they published a description of what was later called the "back-rolling wonder"(Clausen, 1927). Jumping is achieved by the contraction of large muscles which pull on large blocks of resilin which store the resultant energy. When triggered the energy is released pulling the thorax in such a way that it becomes shorter and the mesonotum arches upwards at the scuto-scutellar suture; this, in turn, pulls the mid coxae inwards (via a tendon-like muscle) which results in a sudden kick of the mid legs causing an explosive jump (Gibson, 1986). A similar but not so well developed mechanism is also found in the Encyrtidae. Because of these modifications for jumping eupelmines often die in a contorted state with the head and gaster reflexed upwards and often nearly meeting over the thorax. The middle legs are often held in front of the head after death.

Eupelminae

(Phlebopenes pertyi)

|

|

|

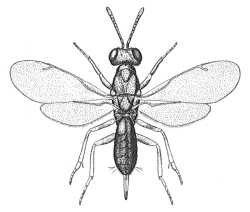

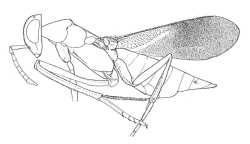

Neanastatinae

(Metapelma sp.)Neanastatinae (Neanastatus cinctiventris) |

Identification

Boucek, 1988 (Australasian genera); Gibson, 1995 (World genera); Kalina, 1981a (European species of Macroneura); Kalina, 1982b (European species of Anastatus); Nikol'skaya, 1952 (Russian species); Peck, Boucek & Hoffer, 1964 (Central European genera).

References

Askew, R.R. 1961. Eupelmus urozonus Dalman (Hym. Chalcidoidea) as a parasite in cynipid oak galls. Entomologist 94:196-201.

Boucek, Z. 1988. Australasian Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). A biosystematic revision of genera of fourteen families, with a reclassification of species :832pp.. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, U.K., Cambrian News Ltd; Aberystwyth, Wales.

Burks, B.D. 1979. Torymidae (Agaoninae) and all other families of Chalcidoidea (excluding Encyrtidae). (In: Krombein, K.V.; Hurd, P.D. jr.; Smith, D.R.; Burks, B.D., Editors.) Catalogue of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico 1:748-749, 768-889, 967-1043. Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington, D.C.

Clancy, D.W. 1946. The insect parasites of Chrysopidae (Neuroptera). Univ. Calif. Publs Ent. 7:403-496.

Clausen, C.P. 1927. The bionomics of Anastatus albitarsis Ashm., parasitic in the eggs of Dictyoploca japonica Moore (Hymen.). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 20(4):461-472, one plate.

Gibson, G.A.P. 1986. Mesothoracic skeletomusculature and mechanics of flight and jumping in Eupelminae (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea: Eupelmidae). Canadian Entomologist 118(7):691-728.

Gibson, G.A.P. 1995. Parasitic wasps of the subfamily Eupelminae: classification and revision of world genera (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea: Eupelmidae). Memoirs on Entomology, International 5:v+421pp.

Kalina, V. 1981a. The Palaearctic species of the genus Anastatus Motschulsky, 1860 (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea, Eupelmidae) with descriptions of new species. Silvaecultura Tropica et Subtropica, Prague 8:3-25.

Kalina, V. 1981b. The Palaearctic species of the genus Macroneura Walker, 1837 (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea, Eupelmidae), with descriptions of new species. Sb. Vedeck. Lesnick. Ust. Vysoke Skoly Zemed. v Praze 24:83-111.

Morris, H.M. 1938. Annual report of the entomologist for 1937. Ann. Rep. Dep. Agric. Cyprus 1937:42-47.

Muesebeck, C.F.W. & Dohanian, S.M. 1927. A study in hyperparasitism, with particular reference to the parasites of Apanteles melanoscelus (Ratzeburg). Bull. U.S. Dep. Agric. No 1487:35pp.

Nikol'skaya, M. 1952. Chalcids of the fauna of the USSR (Chalcidoidea). Opredeliteli po Faune SSSR, Izdavaemie Zoologicheskim Institutom Akademii Nauk SSR 44:575pp. Akademiya Nauk SSSR, Moscow and Leningrad. (In Russian; English translation: 1963: Israeli Prog. for Scient. Transl., Jerusalem 593pp)

Peck, O., Boucek, Z. & Hoffer, A. 1964. Keys to the Chalcidoidea of Czechoslovakia (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada No 34:170pp, 289 figs.

Phillips, W.J. & Poos, F.W. 1921. Life-history studies of three jointworm parasites. Journal of Agricultural Research 21(6):405-426.

Taylor, T.H.C. 1937. The biological control of an insect in Fiji. An account of the coconut leaf-mining beetle and its parasite complex: 239pp, 23 plates. Commonwealth Institute of Entomology, London.

Walsh, B.D. & Riley, C.V. 1869. The joint worm (Isosoma hordei Harris). American Entomologist 1:149-158.

Last updated 07-Jun-2004 Dr B R Pitkin