Nose picking might be thought of as a socially unacceptable behaviour among humans but amazingly we are one of 12 species of primate to exhibit this habit! Today a new paper has revealed this behaviour in aye-ayes for the first time.

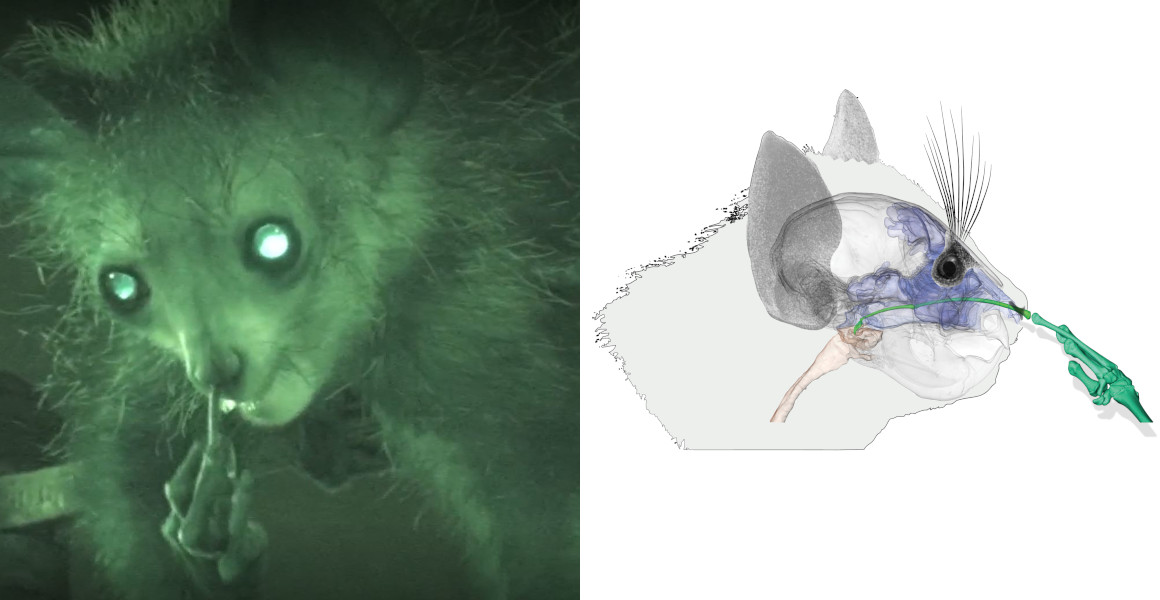

The eight-centimetre-long finger of the aye-aye can reach through its nose to the back of its throat, with the animals seen licking off the gathered mucus. Image © Anne-Claire Fabre/Renaud Boistel

The aye-aye is a species of strepsirrhine primate closely related to lemurs and the largest nocturnal primate in the world. In folklore they have received an ugly and undeserved reputation as harbingers of death and as such have often been killed on sight in some countries. The myth in part comes from their highly specialized and elongated finger, that legend says they use to point at those marked for death.

In truth, the third and fourth fingers (middle and ring fingers) of the aye-aye are elongated and skinny and are highly specialised to help them feed. Amazingly the fingers make up about 65% of the length of the hand with the hand itself making up over 40% of the total length of the forelimb. Aye-ayes use these adaptations to find food by tapping on wood, generating acoustic reverberations, which allow them to locate grubs inside which they can then extract with the specialised digits.

Lead author Anne-Claire Fabre is curator of mammals at the Naturhistorisches Museum der Burgergemeinde Bern and associate professor at the University of Bern, as well as a Scientific Associate of the Natural History Museum. She noticed the more novel use of the aye-aye’s long middle finger when filming their behaviour at the Duke Lemur center, a research foundation in North Carolina.

Anne-Claire, says, ‘It was impossible not to notice this aye-aye picking its nose. This was not just a one-off behaviour but something that it was fully engaged in, inserting its extremely long finger a surprisingly long way down its nose and then sampling whatever it dug up by licking its finger clean!’

‘There is very little evidence about why we, and other animals, pick our nose. Nearly all the papers that you can find were written as jokes. Of the serious studies, there are a few in the field of psychology, but for biology there's hardly anything. One study shows that picking your nose can spread bacteria such as Staphylococcus, while another shows that people who eat their own snot have fewer dental cavities.’

Previous studies on the subject have suggested that the ingestion of nasal mucus could play an important role in the immune system and also it could prevent bacteria from sticking to tooth surfaces therefore improving oral health.

This new paper aims to consolidate the few research papers that cover nose-picking in primates into one place as well as providing photographic and video evidence of the behaviour in aye-ayes for the first time. In doing this the team discovered that nose picking has been documented in at least 12 primate species including humans, chimpanzees and orangutans.

To better understand this behaviour the research team also CT-scanned the skull and hand of an aye-aye specimen to reconstruct the position of the middle finger inside the nasal cavity. These reconstructions suggested that the finger is likely to descend all the way into the throat.

Roberto Portela Miguez, Senior Curator in Charge, Mammals, at the Museum and a co-author on the new paper says, ‘It is great to see how museum specimens and digital methods can help us elucidate behaviours that are generally quite difficult to observe in their natural habitat. We hope that future studies will build on this work and help us understand why we and our closest relatives insist on picking our noses!’

‘Aye-ayes are highly endangered, and really need our help. Papers like this can hopefully help draw attention to the species, highlight how little we may know about them and get more people to support their conservation.’

A final observation the team cited is that primates love for ingesting their own mucus may simply be down to its texture, crunchiness and saltiness meaning this clever trick may reward them with a treat!

The study A review of nose picking in primates with new evidence of

its occurrence in Daubentonia madagascariensis is published in the Journal of Zoology.

Notes to editors

Natural History Media contact:

Tel: +44 (0)20 7942 5654 / 07799690151

Email: press@nhm.ac.uk

Images and video available to download here.

The Natural History Museum is both a world-leading science research centre and the most-visited natural history museum in Europe. With a vision of a future in which both people and the planet thrive, it is uniquely positioned to be a powerful champion for balancing humanity’s needs with those of the natural world.

It is custodian of one of the world’s most important scientific collections comprising over 80 million specimens. The scale of this collection enables researchers from all over the world to document how species have and continue to respond to environmental changes - which is vital in helping predict what might happen in the future and informing future policies and plans to help the planet.

The Museum’s 300 scientists continue to represent one of the largest groups in the world studying and enabling research into every aspect of the natural world. Their science is contributing critical data to help the global fight to save the future of the planet from the major threats of climate change and biodiversity loss through to finding solutions such as the sustainable extraction of natural resources.

The Museum uses its enormous global reach and influence to meet its mission to create advocates for the planet - to inform, inspire and empower everyone to make a difference for nature. We welcome over five million visitors each year; our digital output reaches hundreds of thousands of people in over 200 countries each month and our touring exhibitions have been seen by around 30 million people in the last 10 years.

Contact

Weekdays: +44 (0)20 7942 5654

Evenings and weekends:

+44 (0)7799 690 151

Email: press@nhm.ac.uk

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media