Scientific knowledge of the rarely seen spectacled porpoise is extremely limited.

So the new addition to the Museum's research collections is set to offer a rare insight into the lives of these elusive cetaceans.

Mammals curator Richard Sabin shows prize draw winners Rebecca and Katherine one of the exciting finds on the Museum's new spectacled porpoise specimen

Scientific knowledge of the rarely seen spectacled porpoise is extremely limited.

So the new addition to the Museum's research collections is set to offer a rare insight into the lives of these elusive cetaceans.

In January 2017, a spectacled porpoise (Phocoena dioptrica) stranded on the coast of the Falkland Islands.

A team from Falklands Conservation promptly froze the small cetacean and offered it to the Museum as a new specimen for the research collections.

There are around 90 described cetacean species in the world. The Museum's recent acquisition offers scientists a unique opportunity to solve some of the mysteries surrounding one of the least-known of all of these.

At an off-site facility, the porpoise's new life at the Museum began with a detailed surface examination from mammal curators Richard Sabin and Louise Tomsett.

In the newly built Large Vertebrate Preparation Facility at an off-site Museum location, the spectacled porpoise made its scientific debut.

Because so little is known about the species, any small detail may hold imperative information about the lives of these rare marine mammals.

The scientists found a blow fly, eggs and larvae on the specimen, as well as algae on the dorsal fin and an ectoparasite

Richard says, 'We know very little about their diets. We know hardly anything about their distribution and migration.

'But these are the sorts of things that, due to the techniques we now have, we can extract from this specimen.'

But before any in-depth and invasive procedures such as dissection can be carried out, the scientists completed a thorough surface examination.

Aside from the pungent smell of the dead porpoise, several things were identified almost immediately.

Stuck to its slowly defrosting body was a rather unlucky blow fly that had been caught in the freezing process in the Falklands. Blow fly larvae feed on decaying flesh - in this case the dead porpoise.

Louise and Richard found ample egg and larvae specimens on areas of the body, including in the mouth, in the urogenital opening and under scuffed skin near the dorsal fin.

The fly samples taken were stored in 80% alcohol and will be handed to Museum forensic entomologist Dr Martin Hall, to be examined at a later date.

The team also found a tiny whale louse - a form of ectoparasite - attached to the surface of the skin of the porpoise. As these parasites tend to live on specific species of cetaceans, it could be quite an exciting discovery.

Because the species is so rare, every effort is being made to preserve as much information as possible at each stage of the examination process.

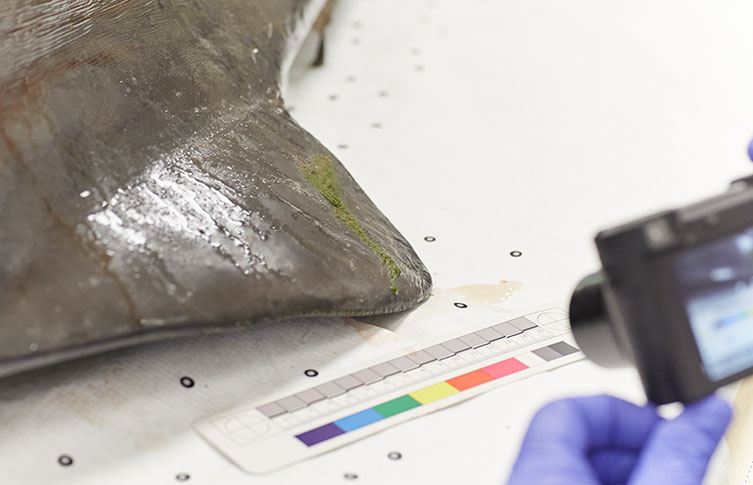

Photos were taken to record sizes, colours and locations of key findings on the cetacean

Richard explains, 'Examination and dissection is a destructive process. We will take dozens and dozens of samples from this specimen as we work through the layers of blubber and muscle tissue.

Amy Scott-Murray works within the Museum's Imaging and Analysis Centre, supporting scientists in their research by using a variety of imaging techniques.

'It's fantastic having Amy working as part of the project team, because she is going to take 3D recordings as we carry out our work.'

For the porpoise, Amy used a technique that is relatively new to the Museum - a 3D-structured light scan.

Using a handheld scanner containing a light projector and camera and slowly moving it over the entire surface of the animal, Amy is able to construct a virtual 3D model of the surface of the porpoise.

Amy says, 'The plan is to scan the whole porpoise before the dissection starts. Then at each stage through the process, I'll scan again, so we end up with a series of scans that we can overlay on each other and virtually look back at later.'

The spectacled porpoise is the first newly acquired specimen to be given this 3D treatment, but it is likely to become standard practice for all new large mammal acquisitions.

Amy uses a handheld 3D scanner to build up virtual images of the specimen that can be used for research in the future

CT scanning will also be carried out on the porpoise's head, giving scientists a unique opportunity to see the untampered with configuration of the cranial tissues.

Richard says, 'We'll be able to see the relationship of all the different parts of the cranial anatomy - the morphology of the brain, the tongue, air sacs, sinuses and the arrangement of soft tissues around the ears. These are things that are lost in traditional preparations and are very difficult to record.

'The applications of the imaging facilities' equipment are endless. It's wonderfully exciting to form research questions and then use the expertise that we have in the Museum to support developing the data to answer them.'

Spectacled porpoises are rarely seen in the wild and can be misidentified at sea. They are believed to live throughout the circumpolar oceanic region surrounding Antarctica.

Sightings are restricted to select areas. The elusive animals are occasionally spotted near Australia, New Zealand, Chile, South Georgia and the Falkland Islands.

They are an oceanic species, although there are records of them in river systems in the southernmost areas of South America.

The scientists collected all of the vital findings from the surface examination, which will then be shared with relevant departments of the Museum for further research

Spectacled porpoises have distinct markings such as dark rings around their eyes - hence their name.

On examining the porpoise Richard says, 'There is a beautiful dark pigmentation around the eyes and mouth, and a very distinct, abrupt separation between the black dorsal and white ventral colouration.

'This is extreme counter-shading, effectively.'

The new spectacled porpoise is likely to hold a range of secrets, which will hopefully also help determine why the animal died.

Falklands Conservation reported the stranded porpoise as an emaciated female. However, the reason for her low weight isn't currently clear.

Richard says, 'We'll determine more about the emaciated state of the animal as we work through the specimen, but there could be a number of reasons.

'It could be that she had given birth to a calf and had been nursing, and having to produce nutrient-rich milk is a big stressor. Cetacean females can lose a lot of body fat when they are nursing their young, and their blubber can reduce in thickness quite dramatically.

'But it could also be that she has a heavy parasite burden, preventing her from feeding effectively. We won't know why she stranded until we've looked inside the specimen.'

Louise prepares containers for collecting the findings. The specimens collected were stored in alcohol and may hold more secrets of the lives of the elusive spectacled porpoise

The Museum only has two other spectacled porpoise specimens in the collection, from 1922 and 1939 respectively. Both are complete skeletons and came with other unique items, including a mummified pectoral flipper, dorsal fin and tail flukes.

Although both are scientifically valuable for comparative studies, the 1939 specimen may be particularly useful because it was also a Falklands stranding.

'Time-series in collections are terrifically important and useful. We can compare the DNA of the two specimens across time to look at any changes in population structure,' says Richard

'By using teeth or soft tissues, we could analyse stable isotopes to see changes in diet or distribution.'

There is a huge amount of information to be gleaned about the spectacled porpoise from the skin down, and Museum scientists are ready to find out more about this elusive cetacean.

Richard says, 'There are so many unknowns with this species. If you were to ask us a question about spectacled porpoises right now, we probably wouldn't know the answer. But we're going to try and find out as much as we can from this specimen.'

Read more about the pioneering work of the Museum's marine scientists.

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media