Nature's spectacular colour palette reaches every corner of the world, from mountain tops to ocean beds.

A watercolour showing a flower crab (Portunus pelagicus), painted by Olivia Tonge in about 1910

But while some bright colours last for hundreds or even thousands of years, this isn’t always the case. What can curators of natural history collections do when specimen colours fade?

The fragility of colour

Colour in some of the Museum's delicate collections can prove challenging to preserve.

Pigments in organisms including plants, birds and fish can decline quickly after an animal dies.

For example, lots of specimens in the Museum's fish collection are brown. When they were living they were a medley of pinks, yellows and blues - but pigments have faded or been lost during the preservation process.

Without these colours, it can be difficult to identify and classify species.

Museum fish curator James Maclaine says, 'The majority of the fish specimens have been pickled in alcohol, which doesn't preserve pigments well.

'Thankfully, alongside the specimens are some incredible illustrations which show very accurately what the animals were like in life, or shortly after death.'

Nature on paper

When it comes to preserving knowledge about the colours of specimens for future generations, the Museum has an immense resource: half a million artworks and prints.

Some of these were created in the nineteenth century by John Reeves, a tea merchant with the East India Company.

He was sent to China in 1812 and spent 19 years living and working in Macao.

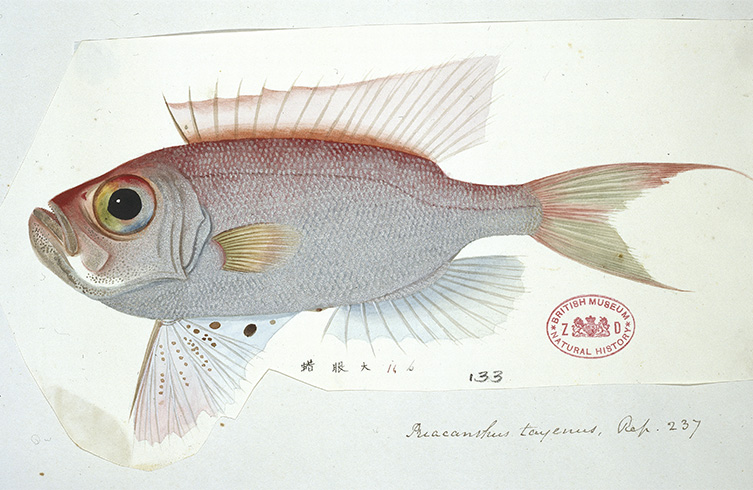

He commissioned Chinese artists to draw plants and animals and taught them to include the distinguishing features of each species in their drawings.

Fish are difficult to draw accurately, as they rapidly lose their natural colours and start to shrink once they are dead.

But the drawings of marine and freshwater fish that Reeves and his artists created capture the specimens in minute detail.

Many of the illustrations they made are now iconotypes, the name given to pictures on which the description and name of a new species are based.

James adds, 'Not only are these illustrations of huge artistic and historical value, they are also very important scientifically. Any scientist investigating a species that was first described using the illustration must refer to the iconotype.'

A purple-spotted bigeye (Priacanthus tayenus) from John Reeves' collection

Sarah Bowdich

The Museum's Library and Archives are home to artworks by hundreds of illustrators, naturalists and painters.

Some artists became scientific experts in their own right, thanks to hours of patient study.

Sarah Bowdich (1791-1856) was an author, illustrator and traveller, and became a scientific explorer on an equal footing with her husband.

She popularised science and illustrated many of her own books, becoming the first European woman to meticulously collect plants for scientific study in tropical West Africa.

Sarah Bowdich sat on riverbanks to paint freshwater fishes like this perch (from the family Percidae)

Andrea Hart, Head of the Museum Library's special collections, takes care of Bowdich's drawings in our Archives.

She says, 'Nineteenth-century scientists were already aware that colour needed to be recorded quickly, if they were going to capture a true likeness of the living creature.

'Bowdich observed her fish subjects while they were still fresh on the river bank, so that she could record their true colours before their vitality diminished.'

Artistic license

Andrea points out that even drawings intended to be scientific records have limitations.

The Museum Library holds 16 sketchbooks by Olivia Tonge, who worked in India between 1908 and 1913.

Her sketchbooks contain vibrant watercolour paintings, but her colours may not necessarily be true to the living creatures.

Drawings by Olivia Tonge

Andrea says, 'Tonge used sketchbooks with a variety of coloured paper inside them. Her work is amazing because she used the paper to its best advantage and showed off the colour of her subjects.

'But the finer detail of the images may not be scientifically accurate, because she is very artistic in her representations of the natural world.

'Each artist's work is different, depending on their skill, style, level of knowledge and reasons for drawing.'

The Bauer brothers

The Bauer brothers attempted to make their work as accurate as possible by creating colour charts.

Ferdinand (1760-1826) and Franz Bauer (1758-1840) were among the best natural history artists of all time. Their obsession with colour is evident in their work.

Ferdinand recreated the true colour of specimens by assigning each shade a four-digit number, and recorded the various codes in his sketches.

A pair of hooded parrots painted by Ferdinand Bauer

It meant he could turn sketches into paintings at a later date, and the reproduction of colour in the finished watercolours would be more accurate.

Andrea says, 'He really showed off the skill that was needed in the scientific community.

'The colour charts were like our modern Pantone charts, which standardise colour reproduction. The colours would have been just as accurate as the anatomical and morphological detail required to identify a species.'

The Bauer brothers were also able to draw minute details of plants that are not normally visible without a microscope or dissection.

Franz recorded new plant species sent from across the world to be grown at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew. He specialised in orchids, using microscopes to study and differentiate species.

This work was particularly important in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when many species that were new to science were being discovered.

The drawbacks of artwork

Creating an accurate drawing of a specimen does not guarantee that a record of its appearance will be preserved.

Curators engage in a constant battle to keep artworks safe and protected from the elements.

Andrea says, 'We have to be very careful when curating and displaying these beautiful artworks.

'We have humidity and temperature controls to protect the paper, as well as light controls.

'Light affects watercolours much more heavily than paints like oil, with blue and pink pigments most likely to fade. Unless letters, paintings and drawing are digitised, you still run the risk of losing them over time.

'Although photography has helped us in that regard, it has its limitations and cannot replace an artist's eye. The need for scientific illustration continues to exist in research, and is still used as a tool for identifying species.

'It allows for different parts of an organism to be shown in far greater detail than a photo.'

See beautiful artwork

Enjoy stunning natural history illustrations in our Images of Nature gallery

Library and Archives collection

The Museum’s Library and Archives maintains the world’s finest collection of natural history literature, artwork and manuscripts.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media