Parrotfish often chomp on rocks and crunchy coral exoskeletons.

When they ingest this hard material, it must go somewhere. But where?

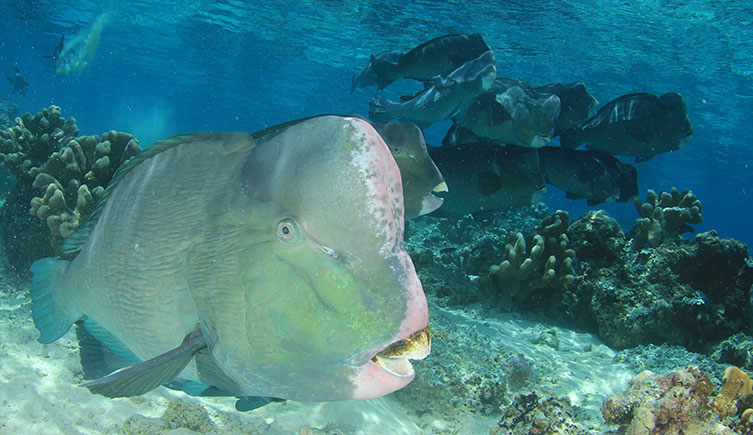

There are about 100 species of parrotfish. This is the green humphead parrotfish, Bolbometopon muricatum, which is one of the larger species. © Rich Carey/ Shutterstock

Parrotfish often chomp on rocks and crunchy coral exoskeletons.

When they ingest this hard material, it must go somewhere. But where?

While relaxing on an endless white, sandy beach might be your idea of a perfect getaway, you should know that some proportion of that stunning sand may have been pooped out by a parrotfish.

There are about 100 species of parrotfish. They belong to the Scaridae family and live on coral reefs, seagrass beds and rocky coastlines. They are named after their beak-like mouthparts, which are actually a set of protruding, fused teeth.

This is the daisy parrotfish, Chlorurus sordidus. They're found in tropical waters in the Indo-Pacific Ocean, where they feed mostly on algae. © Miroslav Halama/ Shutterstock

Parrotfish will sometimes eat dead organic matter, seagrasses, sponges and other small marine invertebrates, but they mostly feed on algae. This serves an important function on reefs because it stops the algae from growing too much and outcompeting the coral for resources such as light.

While many parrotfish will trim algae by scraping it away from the surface it’s attached to, some larger species such as the bumphead parrotfish, Bolbometopon muricatum, which can grow up to 1.3 metres long, have a taste for coral too.

Though it often looks like colourful rock, coral is actually made of colonies of marine animals related to sea anemones, that secrete a hard exoskeleton around themselves as they grow. Its exoskeleton is made of calcium carbonate like the shells of other marine organisms such as clams and sea snails.

Corals acquire symbiotic zooxanthellae algae from their surrounding environment. The coral provides shelter as well as nutrients for the algae to use in photosynthesis, and in return the algae produce sugars that help feed the coral. This is known as a mutualistic relationship.

Large parrotfish will gouge into the coral’s exoskeleton, using their teeth to excavate their meals. It’s been estimated that a bumphead parrotfish can take over 4.5 tonnes of reef material each year and that coral can make up more than half of its diet.

The idea of crunching on hardened coral might sound unpleasant, but it’s no issue for a parrotfish. Their teeth are made of fluorapatite, which scores five out of 10 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness. That means they’re harder than substances like gold, which rates as 2.5-3 on the scale and iron, which is 4 on the scale.

Parrotfish also continually grow new teeth to replace those worn down over time.

The parrotfish's large beak is actually a set of protruding teeth © Rich Carey/ Shutterstock

Parrotfish don’t have large chunks of rock, coral or other substrate rumbling through their guts. A set of pharyngeal jaws at the back of their throat helps them extract the digestible bits and grind the rest of the material up into tiny, passable grains.

Most bony fishes have pharyngeal jaws, but they don’t all use them for the same thing. Moray eels, for example, have pharyngeal jaws loaded with sharp, backwards facing teeth that they use to pull prey down their gullet.

For parrotfish, the fine sand they mill with their pharyngeal jaws is excreted and becomes material that forms the seafloor, providing an important habitat for marine animals, as well as becoming part of the beaches we enjoy.

Coral sand, also referred to as biogenic sand, isn’t just made up of material that’s passed through a parrotfish. The movement of the ocean is abrasive and can also wear down calcium carbonate structures over time, slowly turning them to sand. Many other organisms also contribute to bioerosion, such as sea urchins, sponges and worms.

When the calcium carbonate exoskeletons of sea urchins break down, like coral, they can contribute to biogenic sand. © Damsea/ Shutterstock

Sand comes in a variety of forms, from both land and sea. Abiogenic sand comes from non-living sources, such as rocks that have broken down through weathering or erosion. Materials such as quartz, the volcanic rock basalt and human-made materials, such as sea glass, are also common components of sand.

Biogenic sand is made up of bits of once-living organisms. Coral fragments are one contributor but foraminifera, mollusc shells and sea urchin spines are also common in biogenic sand.

Beaches made of coral sand that have no input from other types of sand, such as quartz, are quite uncommon. These types of beaches rely on there being coral reefs nearby, which are found close to the equator and generally in warm waters.

Parrotfish are able to produce tonnes of sand each year. In the Caribbean and Hawaii, it’s estimated that up to 70% of beach sand has gone through the guts of parrotfish.

Wherever you next lay down your beach towel, one thing’s for sure, the tiny fragments of rocks, shells and other debris you’re nestling into tells a wonderfully complex story of our peculiar planet.

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Explore life underwater and read about the pioneering work of our marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media