The life of a 166-million-year-old reptile has been turned upside down.

While Marmoretta oxoniensis was believed to have swum in ancient lagoons, new research reveals it spent its time climbing trees instead.

While Marmoretta oxoniensis was believed to have been a swimmer, a closer look at its fossils showed that it actually lived in trees. Public domain image by SeismicShrimp via Wikimedia Commons.

The life of a 166-million-year-old reptile has been turned upside down.

While Marmoretta oxoniensis was believed to have swum in ancient lagoons, new research reveals it spent its time climbing trees instead.

Tiny reptile fossils are revealing more about life in the UK during the time of the dinosaurs.

The Middle Jurassic, which lasted from around 174 to 161 million years ago, was a crucial time in the evolution of life on Earth. Many important groups of animals were diversifying into new forms, but fossils from the period are extremely rare.

While a lot of research has focused on uncovering dinosaurs from this time, the many small reptiles that would have lived alongside them are often overlooked. Fossils of these species are often tiny and poorly preserved, making it hard to know what their lives were like.

One such species is Marmoretta oxoniensis, which is known from fossils found in Oxfordshire and the Isle of Skye. It was discovered alongside the remains of a variety of marine life, so Marmoretta was assumed to have been a semi-aquatic reptile. Modern scanning techniques, however, have shown it would have lived in the trees instead.

Dr David Ford, who has studied early reptiles for his entire career, led the new research into Marmoretta.

“It’s important not just to find out that a species exists, but how it lived,” David says. “By studying animals like Marmoretta, we can infer what was happening during divergences in the evolution of reptiles.”

“Looking at small bones is just as important as looking at a femur that’s a couple of metres long, because we need to understand the whole picture of life – not just the big things.”

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Marmoretta would have lived in an environment somewhat similar to modern mangrove swamps. © Mazur Travel/ Shutterstock

Marmoretta is a stem lepidosaur, an early relative of the group containing all lizards and snakes as well as an unusual reptile known as the tuatara. Lepidosaurs are one of the two main reptile groups alongside the archosaurs, which include crocodiles, birds and dinosaurs.

The lepidosaurs and archosaurs are believed to have split apart around 260 million years ago during the Late Permian, but there are very few well-preserved fossils of the early members of either group. As a result, it’s hard to know what the lifestyles of the first lepidosaurs were like.

“In the main, all that’s left of these animals are quite small and fragile fossils that we haven’t had the technology to delve into until recently,” David explains. “In the past, they would have been put into acid baths and slowly extracted from the rock they were embedded in.”

“While the bones could then be looked at under a microscope, the association between the different parts of the skeleton would have been lost.”

Developments in scanning technology, however, are now turning things around. CT scans allow palaeontologists to examine bones while they’re still in the rock, while synchrotron radiation uses powerful X-rays to examine the fossils in fine detail.

As these technologies have become more widespread, it’s become easier and cheaper for scientists to apply them to fossils like Marmoretta. Its fossils are extremely delicate - the skull is just two centimetres from end to end, while the individual finger bones are millimetres long.

“If we’d prepared this tiny fossil traditionally, we never would have understood the ecology of Marmoretta,” David adds. “By using synchrotron scanning, we were able to get incredibly fine resolution that has allowed us to draw new conclusions about its lifestyle.”

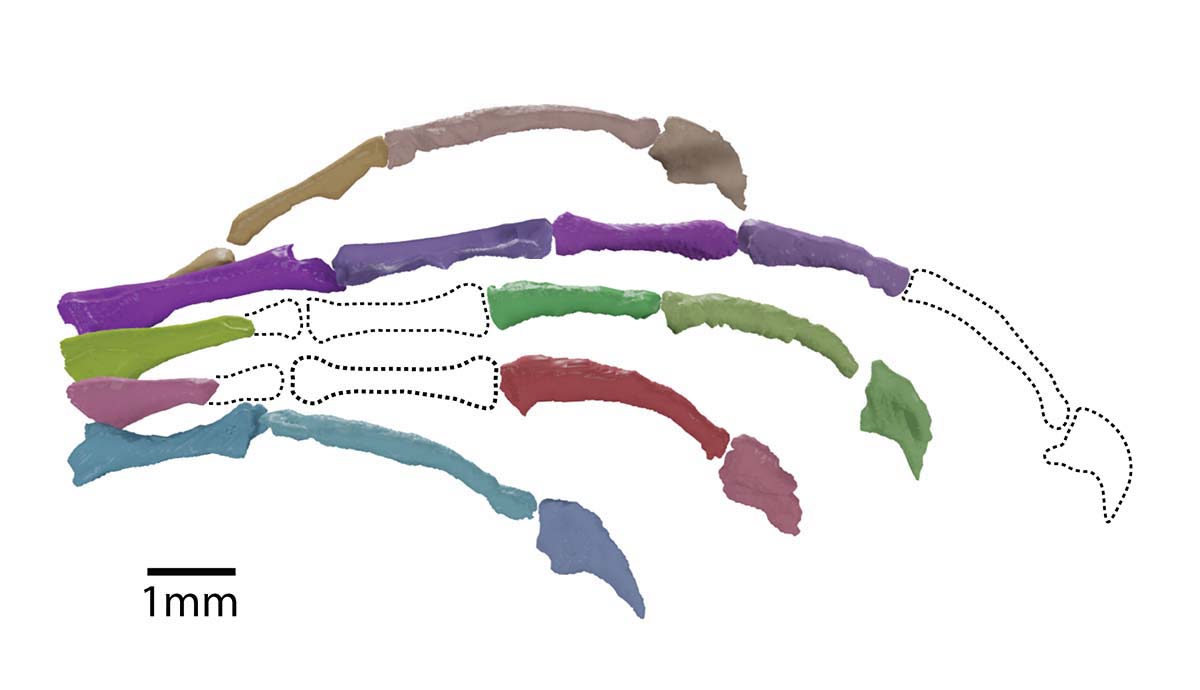

The curved bones near the end of Marmoretta's hand would have helped it to grasp the trunks and branches of trees. Adapted from © Ford et al.

Looking at the scans of the fossil, the team noticed that the hands were not those of an aquatic reptile. Many swimming reptiles of this period would be expected to have flattened fingers or webbing between its digits to provide a paddle-like surface to push through the water with.

Instead, Marmoretta has long and curved bones near the end of its fingers. These are a distinctive sign of climbing reptiles, as the curves help them to grip to a tree’s trunk and branches.

Its spine would also have been stiffer than those of many aquatic reptiles, which would have helped Marmoretta to keep its balance when climbing high above the ground. This alone, however, wasn’t enough to be certain about its lifestyle.

“While it certainly looked like Marmoretta was a climbing animal, we needed to provide evidence based on the morphology of the preserved bones” David says. “So, we compared the measurements of its bones with living reptiles to argue, using statistical analyses, that it did spend at least part of its life in trees.”

“We developed a new method to help show this, and we’re hoping that it will be useful for other researchers looking at the ecology of small, early reptiles.”

The team’s comparisons suggest that Marmoretta would have spent its days living in trees around the edge of a subtropical lagoon, somewhat similar to coastal mangrove swamps that can be found around the tropics today.

It seems likely that Marmoretta and its relatives moved into the trees to avoid potential predators on the ground. This might be one reason that lizards are still thriving more than 160 million years later.

“Taking advantage of the vertical realm could have been the secret of these animals’ survival,” David adds. “It’s a similar strategy that some small mammals used in the Triassic as well, so it certainly seems to have its benefits.”

“As we continue to investigate early reptiles, we’ll have a much better idea of the diverse ways they came to be such a big part of life on our planet. There’s still a lot to learn, but our knowledge of reptile evolution is improving all the time.”

Find out what Museum scientists are revealing about how dinosaurs looked, lived and behaved.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media