Laurent Ballesta has won the Grand Title in this year’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year for the second time with an ethereal picture of a shimmering golden horseshoe crab.

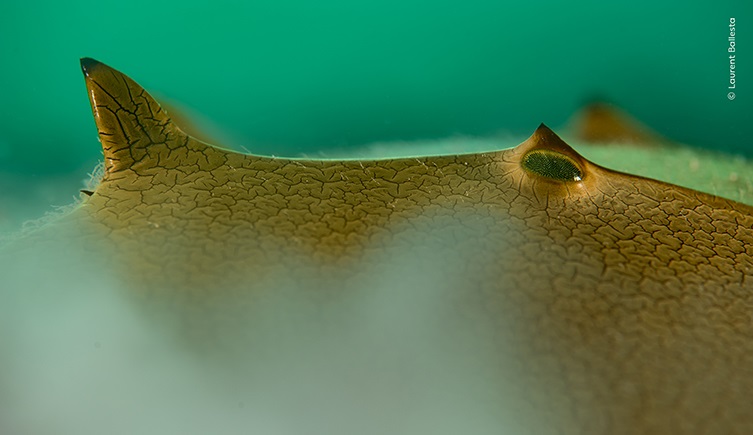

The Golden Horseshoe by Laurent Ballesta has been awarded this year's Grand Title prize. ©Laurent Ballesta

Cruising along the seabed in the protected waters of Pangatalan Island in the Philippines, a horseshoe crab is accompanied by a trio of golden trevallies.

The image, titled The Golden Horseshoe, has won Laurent Ballesta his second Wildlife Photographer of the Year Grand Title award in three years, having won in 2021 with another stunning image of mating camouflage groupers.

This time around Laurent turned his focus to the Endangered tri-spine horseshoe crab as part of a series of images for the competition's Portfolio Award. Documenting these extraordinary animals - barely changed for roughly 100 million years - as they scuttle through the warm waters, feeding, mating and even being home to other animals, Laurent has shown them in an entirely new light.

Looking almost like an extraterrestrial spaceship, the gilded carapace of the arthropod gliding through the dark waters took the judging panel by surprise.

Kathy Moran, the Chair of the jury and editor, says, ‘To see a horseshoe crab so vibrantly alive in its natural habitat, in such a hauntingly beautiful way, was astonishing.’

‘We are looking at an ancient species, highly endangered, and also critical to human health. This photo is luminescent.’

Laurent's winning image is part of a portfolio in which he explores the life of these Endangered creatures. ©Laurent Ballesta

Ancient arthropods

The tri-spine horseshoe crab is typically found living in the tropical waters off southeast Asia. There are actually four living species of horseshoe crabs, three of which can be found in the waters of the Pacific Ocean and one that is found along the Atlantic coastline of North America.

Despite their name, horseshoe crabs are not actually crabs but more closely related to spiders and scorpions. They have a hard external carapace that is split into two parts, while underneath they have five pairs of legs that end in tiny little claws which they use to walk and capture prey.

But the four living species are just a fraction of the diversity of a group of animals whose evolutionary history stretches back an astonishingly long way. The first animals that look superficially like horseshoe crabs appeared way back in the Devonian, around 400 million years ago, when complex plants were only just managing to make it onto land.

These early animals had the characteristic curved shield-like carapace, but whether or not they are classed as horseshoe crabs is open to debate.

Regardless, by 300 million years ago there are fossil animals which do have the characteristic double shield of the modern animals. Appearing during the Carboniferous, many of these early species were not living in marine environments like today’s horseshoe crabs, but were freshwater species instead.

Having survived relatively unchanged for around 100 million years, the tri-spine horseshoe crab is now threatened by humans. ©Laurent Ballesta

Learn from our world-leading experts...

...sign up to our new series of on-demand courses designed for anyone interested in the natural world, regardless of skill level.

Courses now available for £49.99.

Dr Greg Edgecombe is a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum who specialises in the early evolution of arthropods, which includes horseshoe crabs.

‘You can trace a marine lineage of horseshoe crabs from the Devonian right up to the modern,’ explains Greg. ‘But there are two main freshwater radiations that both went extinct.’

‘The trunk that survives is the marine species, but I think that an important part of the story of these animals is that lost diversity, partly in what they were looking like but also in the lost ecologies.’

When it comes to the tri-spine horseshoe crab specifically, there is a fossil from Lebanon dating to 100 million years old that is thought to belong to the same group as the living species. This means that the ancestors of the beautiful golden arthropod photographed by Laurent were swimming around the warm shallow seas whilst Tyrannosaurus rex stalked the land and pterosaurs soared in the skies.

But despite their incredible evolutionary history stretching back hundreds of millions of years, these ancient arthropods are under threat. Their blue blood is critical for the development of vaccines, as it is used to test for potentially dangerous bacterial contamination. In addition to this, many horseshoe crabs are fished to be used as bait to catch other, more valuable species.

This sees hundreds of thousands of the animals harvested every single year. Combined with habitat destruction and ocean pollution, and the future of all four living species are now at risk. Efforts to protect the animals, with plans to replace them in the biomedical sector and moves to protect their breeding grounds, are now underway in many parts of the world.

With any hope, these remarkable survivors will still be swimming the oceans of Earth in 100 million years to come.

The young Wildlife Photographer of the Year

The top prize for Young Photographer of the Year 2023 has gone to Carmel Bechler from Israel, for his striking image of barn owls nesting in an abandoned roadside building. The blaze of neon lights passing the owls as they look out from their roost highlights the growing tension between humans and wildlife as we encroach on habitats.

Owls' Road House by Carmel Bechler is this year's Young Photographer of the Year 2023. ©Carmel Bechler

‘I hope to share with my photography that the beauty of the natural world is all around us, even in places where we least expect it to be, we just need to open our eyes and our minds,’ says Carmel.

Attracting almost 50,000 entries from 95 countries, this year’s competition is once again showcasing some of the most extraordinary images of wildlife, behaviours, and human impacts, including animals being evacuated due to the war in Ukraine, the incredible moment of a snow leopard chasing a Pallas cat and a tony mason bee hard at work building its nest.

Dr Doug Gurr, Director of the Natural History Museum comments, ‘Whilst inspiring absolute awe and wonder, this year’s winning images present compelling evidence of our impact on nature – both positive and negative. Global promises must shift to action to turn the tide on nature’s decline.’

See the exhibition

Book your tickets to see all the winning and runners up images on display in the exhibition at the Museum from Friday 13 October.

Visit the exhibition

Wildlife Photographer of the Year tells the incredible stories of life on our planet through powerful photography and expert insight.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media