Rock boring offers a variety of benefits to bivalves – so why aren't more of them doing it?

A new study reveals that there are many ways these animals bore through solid rock, but a lack of habitat may lock them into an evolutionary dead end.

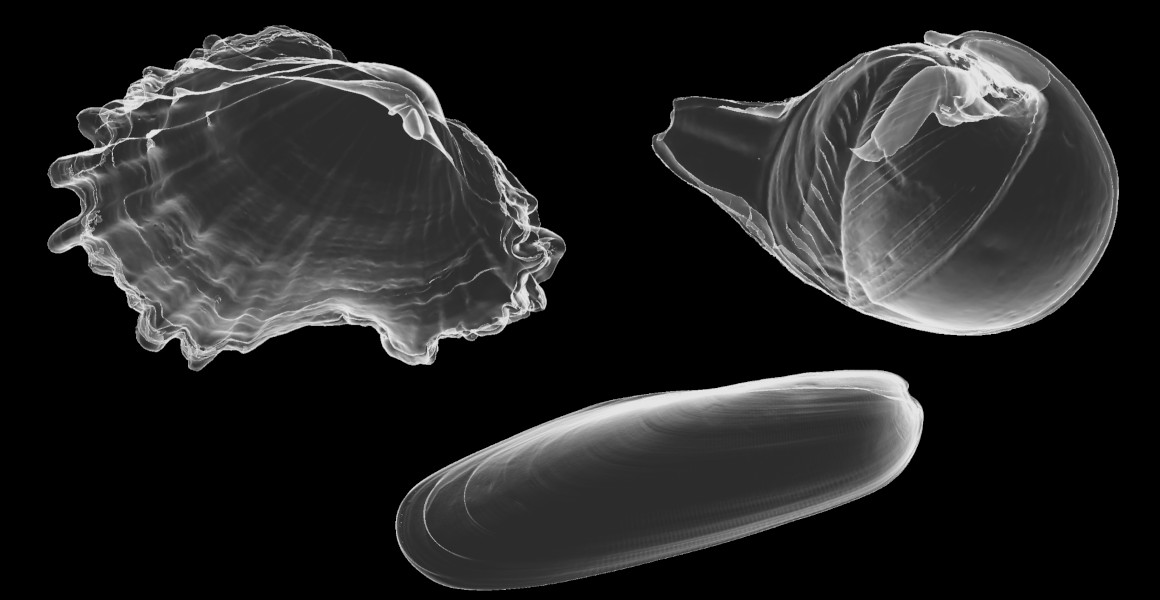

Rock boring bivalves have a diverse variety of shapes and sizes, which researchers did not expect. Image © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

Rock boring offers a variety of benefits to bivalves – so why aren't more of them doing it?

A new study reveals that there are many ways these animals bore through solid rock, but a lack of habitat may lock them into an evolutionary dead end.

Despite their name, boring bivalves are much more exciting than their non-boring relatives.

From giant clams such as Tridacna crocea to small scallops, rock boring bivalves encompass a range of sizes and shapes much larger than their relatives with other lifestyles. Researchers had suspected that they must share some common features for such a complex task, but found that they were wrong.

Dr Katie Collins, who is the Museum's Curator of benthic molluscs and led the research, says, 'What we found was totally unexpected. While we assumed boring molluscs would converge on a small range of forms that were really optimised for this function, this is not the case.'

'Instead, rock-boring bivalves have the greatest range of forms among their relatives, ranging from spheres to cigar and spoon shapes. It seems as though there is no evolutionary reason for these animals to become more similar in shape to make them more optimised for boring, allowing them to maintain a high diversity of forms.'

The findings of the study were published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The mollusc Tridacna crocea is among the smallest of the giant clams, and is able to bore into rock. Image © Hamizan Yusof/Shutterstock

Bivalves are a group of molluscs which live inside a hinged, two-part shell that gives the group their name. As well as being an important source of food for humans and other animals, they also carry out important roles as ecosystem engineers.

Their filter feeding can purify water and remove pollutants such as microplastics, while their burrowing and boring modifies the environment to provide habitats for other species.

These same abilities that allow them to be a positive force in the environment can also make them problematic for human engineering. Undersea telecom cables and concrete foundations can be penetrated by bivalves, causing issues that aren't easily resolved.

The bivalves can do this despite having relatively soft shells made of calcium carbonate, the same material as limestone. To penetrate rocks such as granite and andesite, which are much harder than their shells, these molluscs have had to develop additional methods for boring.

'There are two main methods of rock boring in bivalves,' Katie explains. 'The first is chemical, where they secrete compounds like mucoproteins that act a bit like acids to dissolve rock.'

'Others grind the rocks down mechanically, sometimes making their shells harder by secreting more resilient compounds to help them grind, while others can use fragments of the rock to help them bore.'

Throughout the bivalve group, this ability has evolved eight different times. The researchers wanted to see how this had happened and if it is the result of convergent evolution. This is when organisms that are not closely related share common features to carry out a shared task.

For instance, the streamlined, torpedo-like shape of dolphins and barracuda developed independently because both species rely on swimming fast as part of their lifestyle, and not due to a common inheritance.

The team carried out CT scans of almost 400 bivalve shells held in nine different museums, including the Natural History Museum, the Field Museum and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, to help them investigate.

This paper is part of a larger research program, for which the researchers have scanned around 93% of living bivalve genera, as well as many fossils from across 450 million years, in an effort to answer broader questions about the processes of evolution.

Shipworm are the only rock boring bivalves which have moved on to a different food source. Image © Irina Nickolaeva/Shutterstock

While the researchers had assumed that the bivalves would have shared common features to carry out the task of boring, they were instead very different.

Just as a variety of species such as woodpeckers, finches and lemurs are capable of extracting prey from bark, it appears there is no one body shape that is especially optimised for rock boring.

'It appears that any ability to bore into rocks, even to a small degree, offers significant benefits,' Katie says. 'Many bivalves burrow into fluid-filled sediment, which requires extremely high amounts of pressure to get into, and pushes back.'

'Rock doesn't fight back like this, so rock borers can grind them down a little at a time and save significant amounts of energy. Of course, this begs a new question - why haven't more bivalves evolved in this direction?'

The researchers believe that there is simply not enough undersea rock to support more bivalves evolving this ability. Most of the seafloor, especially in the deep ocean, is covered in sediment, offering a greater variety of environmental niches for other bivalves to thrive in.

Evolutionary opportunities for boring bivalves tend to be associated with increases in the prevalence and diversity of coral, which offers additional hard surfaces for the molluscs to burrow into.

Boring also appears to be something of an evolutionary dead end, locking bivalves into this singular way of life. Only one group, the shipworms, have ever transitioned from rock boring to another medium, in this case wood, and one species, Lithoredo abatanica, has since gone back the other way.

The lack of specific adaptations needed for rock boring means that despite the relatively low number of species that can do it, this way of life has persisted for hundreds of millions of years. The malacologists' continuing research into these unusual animals could help reveal further insights into the nature of their evolution.

Find out more about why we need to protect the oceans, find themed events, and read about the pioneering work of the Museum's marine scientists.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media