Spectacled caiman and South American false coral snake by Maria Sybilla Merian, 1705

undefinedMaria Sibylla Merian: metamorphosis unmasked by art and science

Kerry Lotzof

Seventeenth-century German artist, scientific illustrator and naturalist, Anna Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717) is best known for her travels and research in Dutch Suriname, South America.

At a time when insects were believed to spring forth magically from mud, waste and plant matter in a process known as 'spontaneous generation', Merian was one of the first to closely observe and record the process of insect metamorphosis.

Her meticulous depictions of metamorphosis, as well as of the tropical flora and fauna of Suriname, caught the attention of the Royal Academy more than 250 years before the first woman was permitted to join.

Portrait of Maria Sibylla Merian from 1679, possibly by Jacob Marrel.

Courtesy of Kunstmuseum Basel.

Maria Sibylla Merian's early life

Merian was born on 2 April 1647 in Frankfurt, Germany, into a family of printers and engravers. When she was three, her father, Matthäus Merian the Elder, passed away. Her mother, Johanna Catharina Sibylla, then married the artist Jacob Marrel, who was known for his highly fashionable flower pieces.

Growing up in Marrel's studio, Merian became highly skilled with watercolours and learned to prepare pigments and copper plates for printing.

Four tulips by Jacob Marrel. Marrel often incorporated small insects to enliven his paintings.

CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

A lifelong fascination with art and science

By age 13, Merian was already a budding artist with a growing curiosity about the natural world. In her journal, she recorded her efforts to rear silkworms and included detailed observations and sketches of their life cycle.

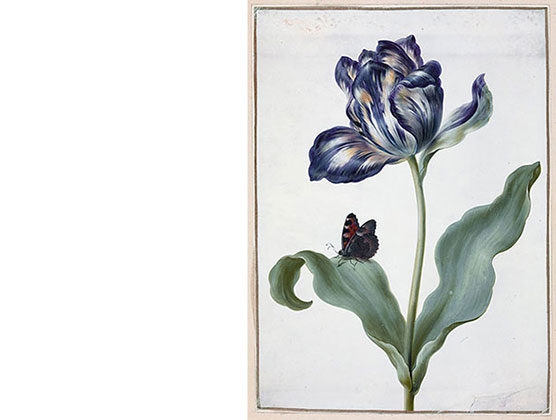

Small tortoiseshell butterfly on a tulip by Maria Sibylla Merian, late seventeenth century

This early inquiry would become a lifelong fascination. Throughout her life Merian painstakingly collected and reared larvae (including caterpillars) and butterflies, observing and recording their life cycles and host plants.

Sometimes a pupa would surprise her by hatching into a swarm of flies or wasps rather than the butterfly or moth she had expected. She recorded this phenomenon as 'false changes', which may be the earliest scientific record of insect parasitism.

Entomology (the study of insects) didn't become a distinct field of science until the nineteenth century.

Merian's marriage

In 1665, aged 18, Merian married one of her stepfather's apprentices, Johann Andreas Graff.

Following the birth of their first daughter, Johanna Helena, the young family moved to Nuremberg in 1670 and opened their own studio.

Provence rose, watercolour on paper by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1675.

Image via Wikimedia commons.

In Nuremberg, Merian worked as a flower painter and engraver, publishing three volumes of flower engravings between 1675 and 1680.

These were the result of her time teaching embroidery to the wealthy daughters of local merchants, which generated important income for the Graff household. The merchants often had greenhouses with exotic flowers from which she created her designs.

Title plate from Maria Sibylla Merian's New Book of Flowers, 1680

Illustration of a Turk's cap lily (Lilium superbum) from Merian's New Book of Flowers, 1680

Merian's flower books became popular guides for botanical watercolour painting and embroidery, two art forms available to women at the time. Merian added insects on almost every page.

Metamorphosis

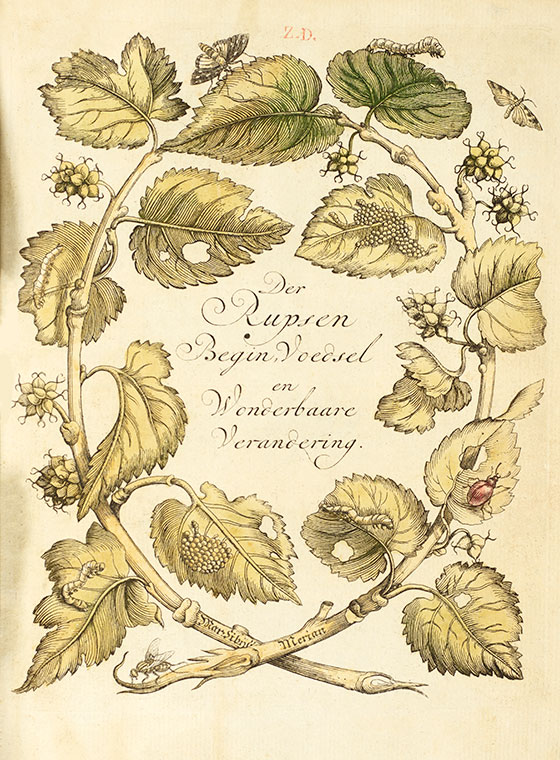

A second daughter, Dorothea Maria, was born in 1678. The following year Merian published her first book on the metamorphosis of European butterflies.

Her first 'caterpillar book' (as she called them) contained 50 copper plate engravings showing the full life cycle of insects and their associated plants.

In an homage to her childhood interest, the title page of Maria Sibylla Merian's first caterpillar book depicts the life cycle of silkworms on a wreath of mulberry leaves, 1679

A Surinamese melon and insects from the book Insects of Suriname by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1726 edition. Throughout her career, Merian's work methodically linked the life cycle of species to the plants they lived and fed on.

Merian was familiar with the work of Jan Goedaert (1617-1668), who also painted insect life cycles, but her approach broke important new ground.

While Goedaert and other contemporaries worked with dried specimens, Merian's depictions of metamorphosis were based on her own meticulous observations of living creatures and the plants that sustained them.

An early forerunner of ecological thinking, Merian's revolutionary approach was only made popular by the taxonomist Carl Linnaeus more than half a century later.

Emperor moth (Arsenura armida) living on the leaves of the coral tree (Erythrina fusca), from Merian's Insects of Suriname, 1705

After the death of her stepfather Jacob Marrell in 1681, Merian returned to Frankfurt to support her mother and escape her own unhappy marriage. From her mother's home she published her second volume on European butterflies in 1683.

Joining the Labadists

In 1685, Merian took her daughters and widowed mother to join the Labadists, a Protestant commune based at Waltha Castle in the Netherlands.

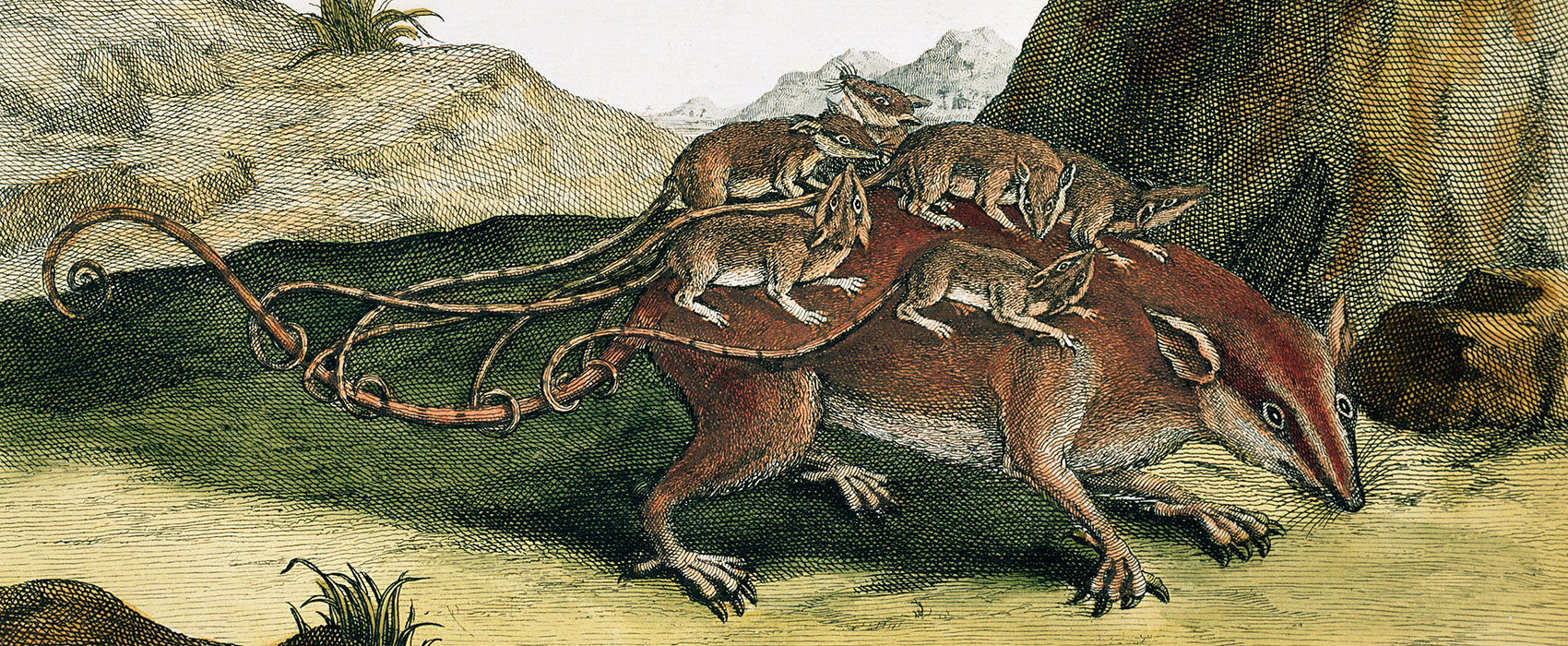

Merian's 'forest rat' or opossum (Didelphimorphia) carrying her young. Detail from plate 66 of Insects of Suriname, 1705. Reproduced as an engraving.

The owner of Waltha Castle, Cornelis van Aersen van Sommelsdijk, had an extensive collection of natural history objects that sparked Merian's interest, including butterflies from the Dutch colony of Suriname.

Although the commune eschewed worldliness, they had a printing press and Merian was able to continue her work.

Holy grounds for divorce

In 1686, her estranged husband Johann visited the commune in an effort to retrieve her. With support from Labadist elders, Merian reasoned that as Johann did not share her faith, their marriage was no longer valid in the eyes of God.

Johann and Merian officially divorced in 1692.

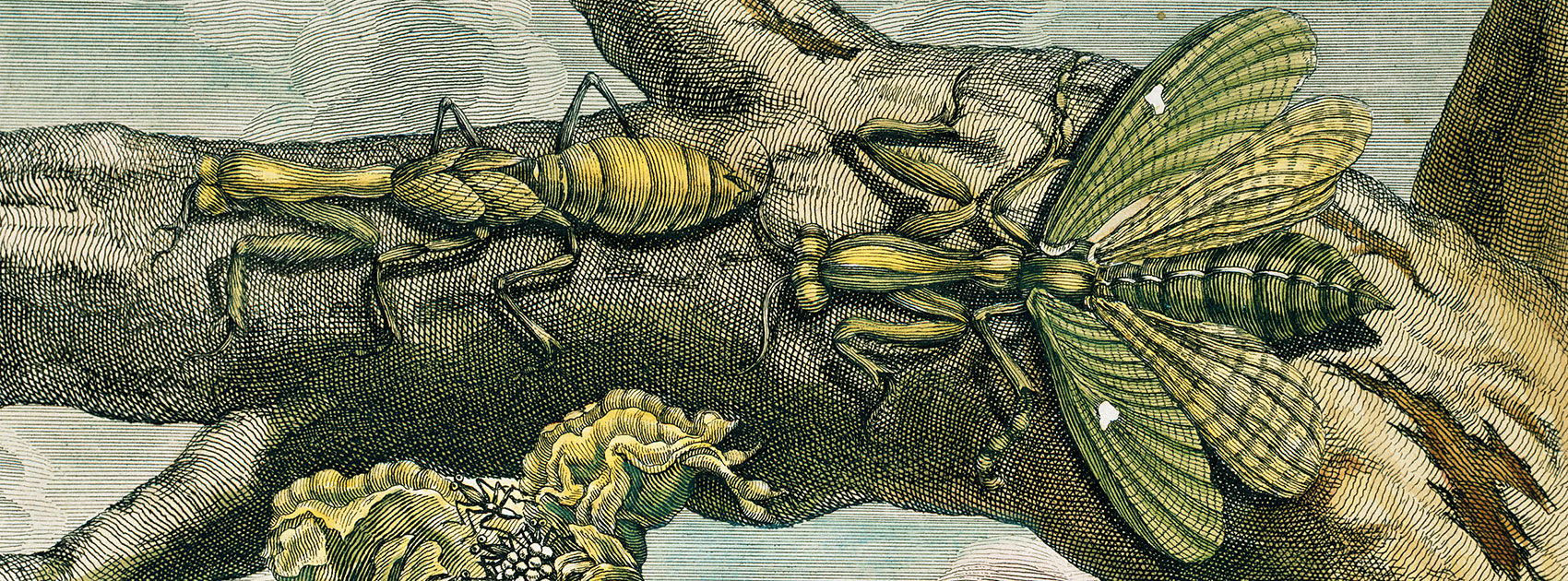

Detail from the life cycle of the praying mantis (Stagmatoptera praecaria) from Merian's Insects of Suriname, plate 66, 1705. Reproduced as an engraving.

Business in Amsterdam

In 1691, following the death of her mother at Waltha Castle the previous year, Merian and her daughters moved to Amsterdam. Under the city's relatively progressive laws, they were able to open their own studio.

The three women worked as independent artists and prepared pigments and specimens for a growing market of collectors.

In cosmopolitan Amsterdam, Merian had access to some of the finest natural history collections in the world. As she mingled with scholars, physicians and botanists, ideas for her own voyage of discovery began to take shape.

Voyage to Suriname

In 1699, aged 52 and accompanied only by her daughter Dorothea, Merian set off on the first-ever purely scientific expedition to the Dutch colony of Suriname.

Undeterred by warnings and social precedent, Merian sold her paintings, prepared her will and (with some help from an influential friend) even secured a small stipend from the Dutch government to help fund her research.

Braving an uncomfortable two-month voyage, the mother-daughter team arrived in Paramaribo and began the overwhelming task of cataloguing the lush tropical flora and fauna of the region.

Merian selected plants primarily for their relationship with the insects they hosted.

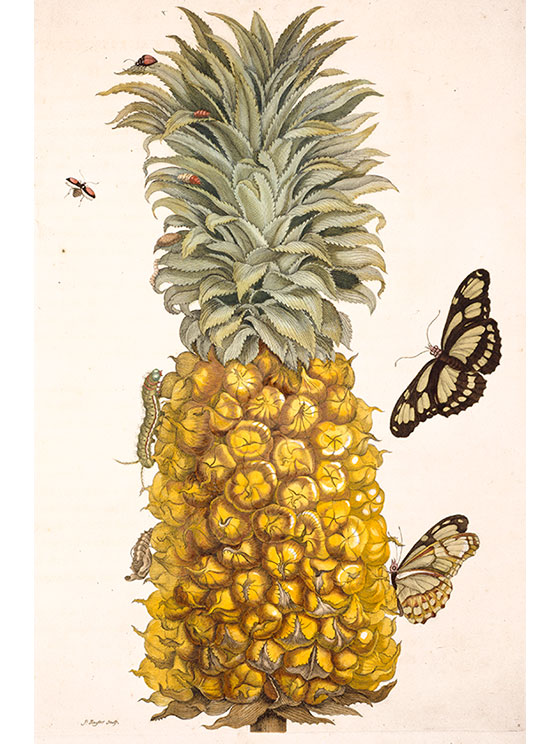

Pineapple (Ananas comosus) and life cycle of the butterfly Philaethria dido, plate 2 of Insects of Suriname, 1705. In her notes, Maria Sibylla Merian enthused about the pineapple's flavour: 'This fruit tastes as though one has mixed grapes, apricots, red currants, apples and pears and were able to taste them all at once […].'

Pomegranate (Punica granatum) with a butterfly's life cycle, plate 9 from Insects of Suriname, 1726 edition

Merian also painted non-entomological subjects such as reptiles, amphibians, spiders and small mammals.

Maria Sibylla Merian captured the curious behaviour of the snake Corallus enhydris, which here curls itself into tight coils and tucks its head out of sight in the shade of a jasmine plant. Detail of plate 46, Insects of Suriname, 1705.

Merian's observations of amphibian life cycles helped to dispel the commonly held belief that frogs sprang directly from mud in 'spontaneous generation'. She was the first to document the life stages of the Surinamese toad (Pipa pipa) which carries its eggs on its back.

Local knowledge

Merian's research in Suriname was made possible by slave labour in the region.

She drew heavily on the local knowledge and assistance of enslaved people, who laboured in terrible conditions on the Dutch sugar plantations of Suriname. Her notes contain candid accounts of their hardship.

Carolina sphinx moth (Manduca sexta) sucking nectar from a peacock flower (Caesalpinia pulcherrima). Other life stages of the moth are present on the plant's stem and leaves. Plate 45 from Insects of Suriname, 1726 edition.

In the text accompanying this illustration of a peacock flower, Merian wrote of the suffering of Suriname's enslaved peoples [warning: readers may find the following excerpt distressing]:

'The Indians, who are not treated well by their Dutch masters, use the seeds to abort their children, so that they will not become slaves like themselves… In fact, they sometimes take their own lives because they are treated so badly, and because they believe they will be born again, free and living in their own land. They told me this themselves.'

Read more about the links between slavery and natural history >

Images of the fantastical creatures of Suriname

In 1701, after two years enduring heat, wet and tropical illness in Suriname, Merian and Dorothea returned to Europe.

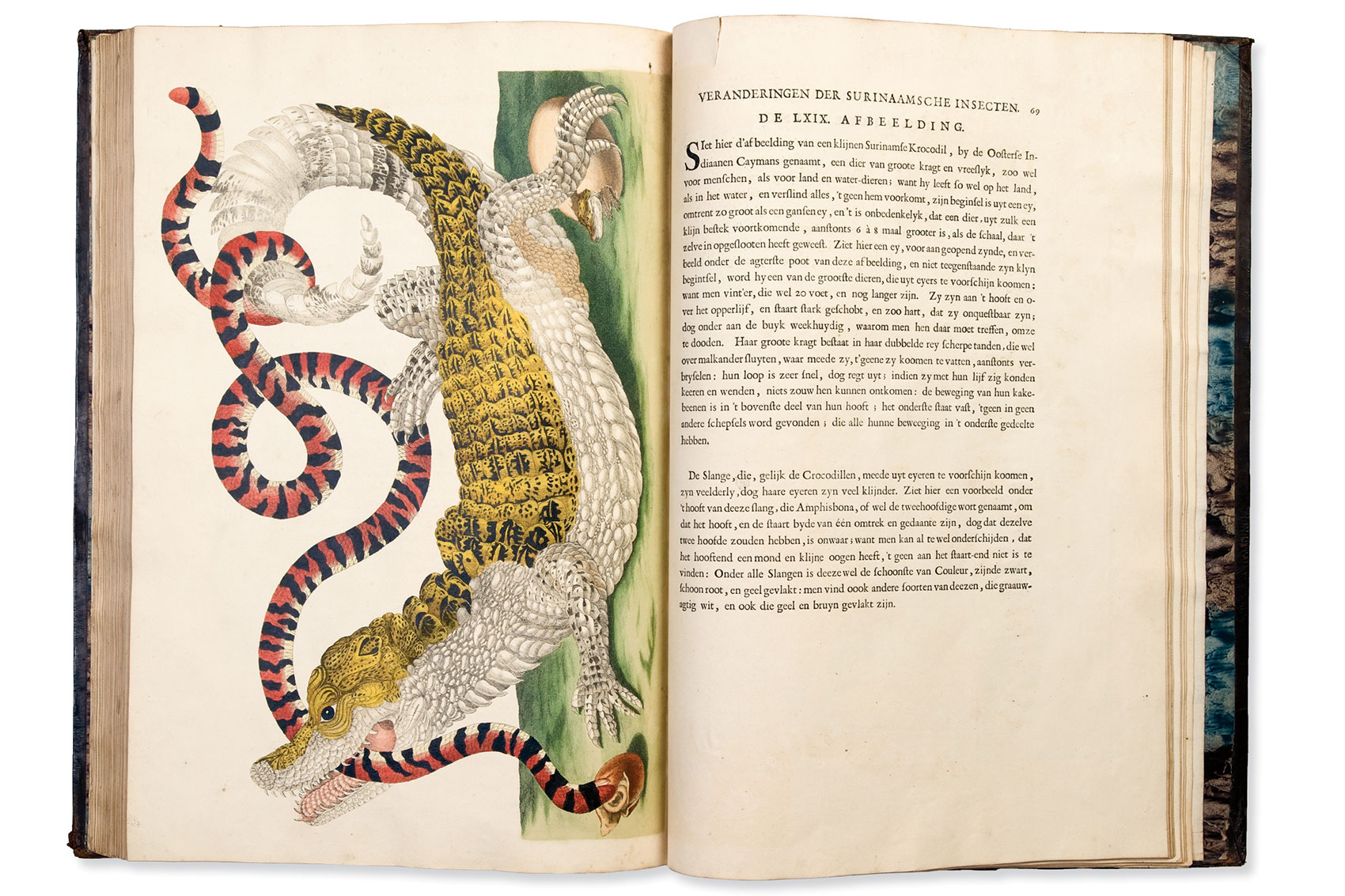

The resulting book on the Insects of Suriname (Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium) was published in 1705. Most of her observations were completely new to Western science.

In Suriname, Merian encountered all kinds of new creatures, including leaf-cutter ants that could form 'living bridges' with their bodies and tarantula spiders large enough to eat small birds. Although some fellow naturalists questioned the accuracy of Merian's work (her creatures seemed too fantastical) she was, for the most part, proven correct.

Detail from plate 18 from Merian's Insects of Suriname showing a pinktoe tarantula (Avicularia avicularia) eating a ruby-topaz hummingbird (Chrysolampis mosquitus)

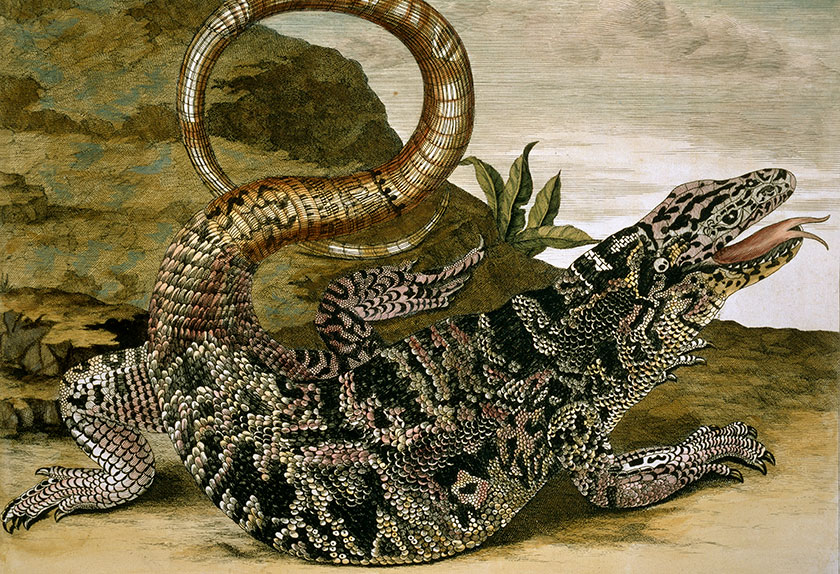

Engraving of a black tegu (Tupinambis teguixin), also known as a golden tegu, adapted from a painting Maria Sibylla Merian made during her Suriname trip

Spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) and South American false coral snake (Anilius scytale) by Maria Sybilla Merian, 1705

Museum copy of Merian's book Insects of Suriname (Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium) shown open at plate 69

Merian's death and legacy

Having never fully recovered from her tropical illness in Suriname, Merian suffered a stroke in 1715 that left her unable to work. She died in poverty two years later, aged 69.

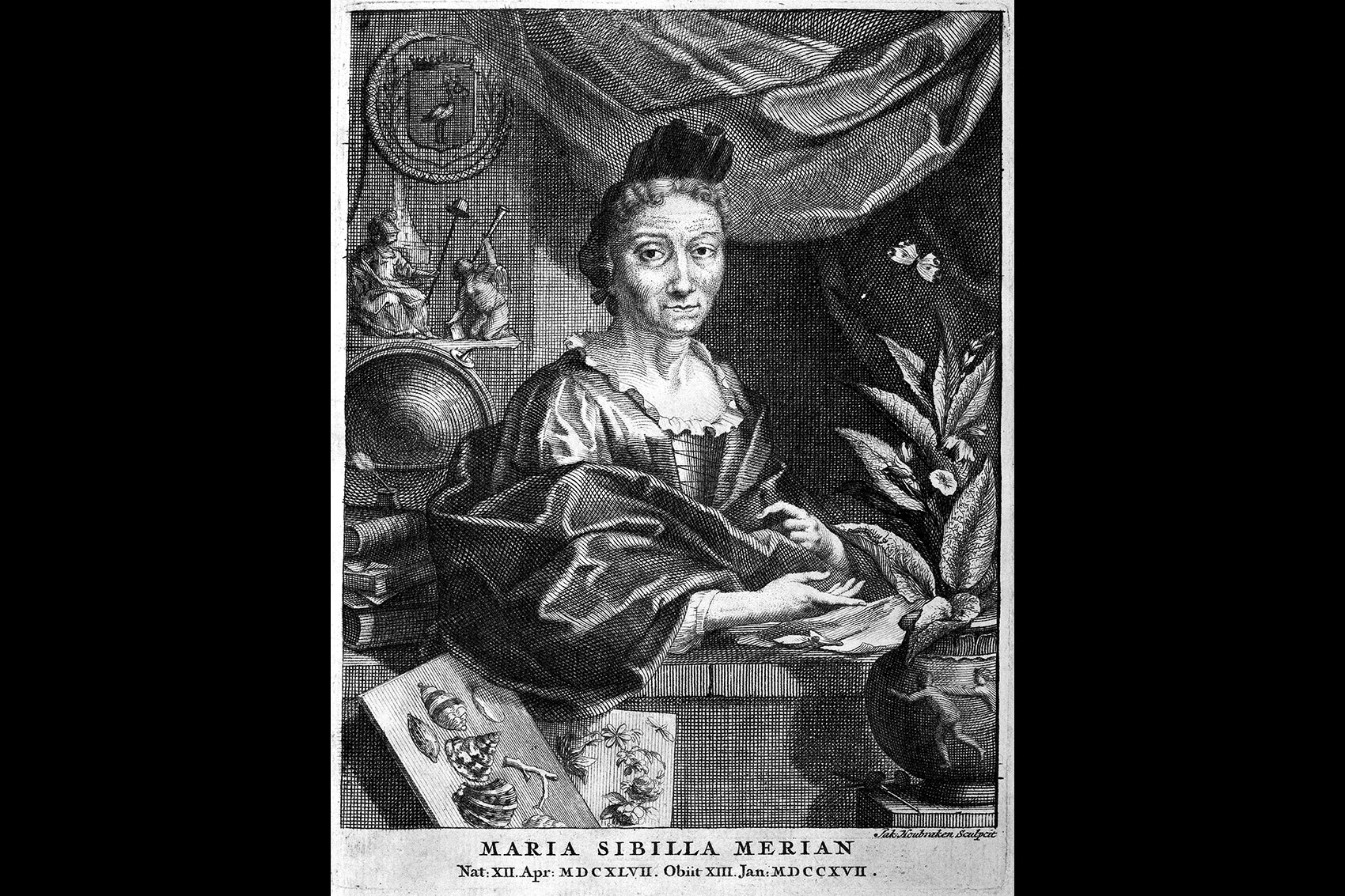

A woman ahead of her time, Maria Sibylla Merian is shown here surrounded by the tools of an artist and natural historian. It appeared in the frontispiece of her book published the year she died.

Merian's pioneering form of natural history illustration earned her a reputation in both scientific and artistic circles.

Her work impressed naturalist and collector Hans Sloane, who purchased a number of her original watercolours, as well as Tsar Peter the Great, who acquired a large collection of her works for his Museum in Russia.

Half a century later, respected taxonomist Carl Linnaeus cited Merian's illustrations for several plants and more than 100 new animal species.Since then at least six plants, nine butterflies, two bugs, one spider and one lizard have been named in her honour.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media