John Edmonstone was a former enslaved man who taught the young Charles Darwin the skill of taxidermy. This skill helped Darwin preserve the birds that fermented his ideas about evolution.

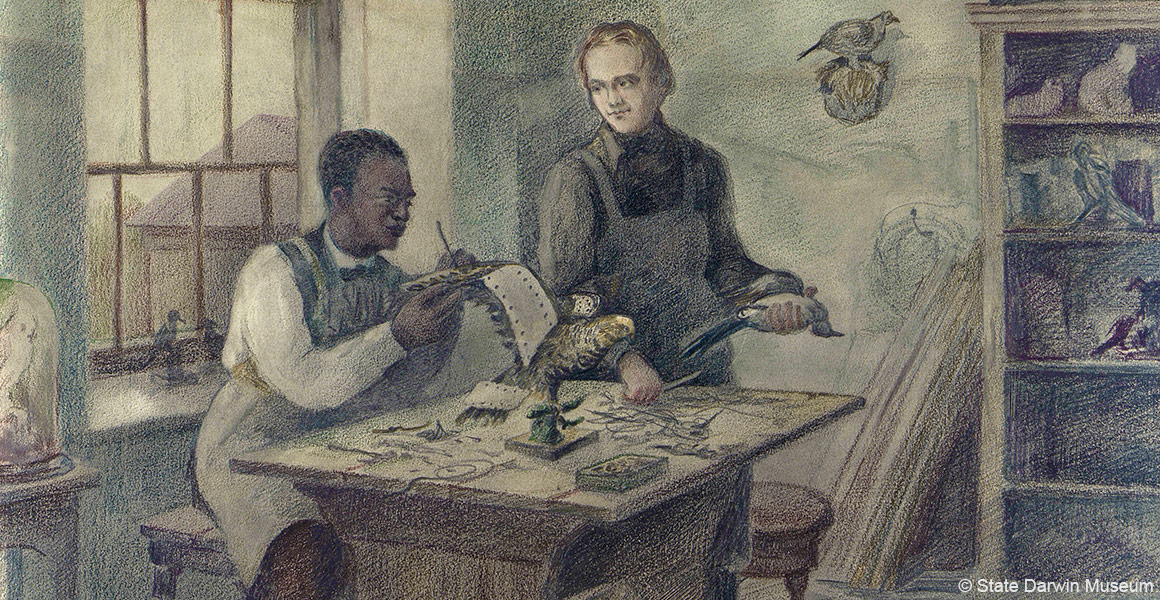

Artist’s impression of John Edmonstone teaching Darwin to preserve birds. © State Darwin Museum

Many Black people’s contributions to science are hidden from history and we have to reconstruct their stories from the margins of more famous naturalists’ lives.

One such intriguing figure is John Edmonstone. A former enslaved Black man from Guyana, John was living in Edinburgh when he met a young Charles Darwin and taught him the skill of taxidermy. This was fundamental to Darwin’s ability to preserve the specimens he collected during his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle.

Though we only have scant details on Edmonstone’s life, what we know reveals that he was a talented and respected taxidermist and naturalist.

Our curator Miranda Lowe tells the story of John Edmonstone, the man who taught Charles Darwin the skill of taxidermy. Discover more contributions of Black people to the field of natural history. Video with audio description (6 minutes 34 seconds).

Edmonstone in Guyana

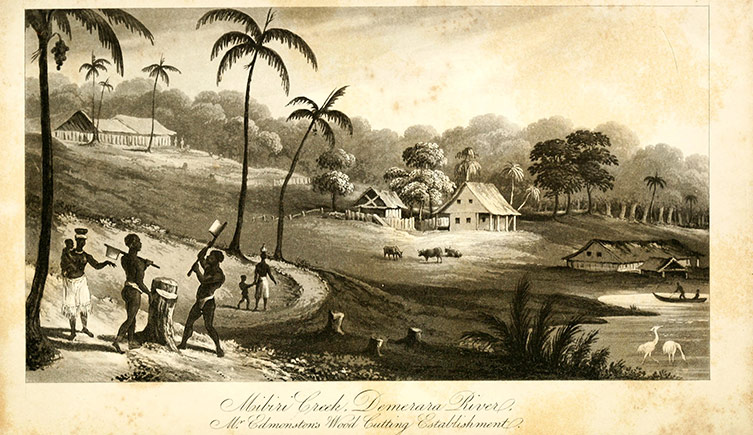

John Edmonstone was born into slavery in Guyana, South America, in 1790. He was enslaved on a timber plantation in Demerara, owned by Scotsman Charles Edmonstone - hence John’s surname. His birth name remains unknown.

The eccentric naturalist Charles Waterton - whose family also enslaved people - visited Charles Edmonstone’s plantation a number of times on his travels through Guyana.

Waterton had developed new methods to preserve bird skins, using toxic mercuric chloride as a fast-acting fixative to stop the animal’s tissues decaying. He taught these techniques to John, who accompanied him on some collecting expeditions.

Despite Waterton believing that John ‘had poor abilities, and it required much time and patience to drive anything into him’, Darwin’s later recollections of John’s skill seems to contradict this assessment.

Charles Edmonstone’s plantation at Mibiri Creek, Demerara River. Image: No known restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Edmonstone in Scotland

Plantation owner Charles Edmonstone returned to Scotland in 1817 and John came with him. Although we don’t know if John was already free when he arrived, he would have become a free man on entering Scotland. Owning slaves was banned in Scotland in 1778 following the case of James Knight.

At first, John lived in Glasgow. By 1824 he was in Edinburgh, making a living for himself working for the University of Edinburgh’s zoological museum and living at 37 Lothian Street.

Edmonstone and Darwin

Darwin went to Edinburgh in 1825 when he was 16 to study medicine, but he didn’t really enjoy the subject and only stayed for two years. While there, he did grow his interest in natural history, attending talks and undertaking his own investigations.

Edinburgh University, 1819.© Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0)

Darwin’s lodgings were at 11 Lothian Street, near Edmonstone’s. Darwin hired Edmonstone to give him private lessons. Though in a letter to his sister it seems price was the main initial motivator: ‘I am going to learn to stuff birds, from a blackamoor I believe an old servant of Dr Duncan: it has the recommendation of cheapness, if it has nothing else’.

Darwin later mentioned in his autobiography:

‘A negro lived in Edinburgh, who had travelled with Waterton, and gained his livelihood by stuffing birds, which he did excellently: he gave me lessons for payment, and I used often to sit with him, for he was a very pleasant and intelligent man.’

Edmonstone charged Darwin one guinea for an hour every day for two months. As well as the time spent on instruction, the two must have conversed on the natural history Edmonstone knew first-hand from South America.

Darwin’s preserved bird specimens

Thanks to Edmonstone’s teachings, Darwin’s preservation skills were put to great use during his voyage on HMS Beagle, from 1831 to 1836. Of the many specimens Darwin collected, almost 500 were bird skins. We hold nearly 200 of these.

Perhaps the most scientifically evocative of the skins are the mockingbirds collected in the Galápagos Islands. It was the Galápagos mockingbirds, rather than the better known finches, that helped precipitate Darwin's thoughts on evolution.

Specimens of Galápagos mockingbirds, collected by Charles Darwin. Darwin began contemplating the differences between species while aboard the Beagle, but it was many years before he came up with his theory for evolution by natural selection.

We can’t be sure that Darwin himself prepared all the bird skins, since specimen preparation was something that was carried out collectively on the Beagle. However, the skills that Darwin learnt from Edmonstone would have been passed down to his assistants.

A life in the margins

There are scant details of Edmonstone’s later life. We know he was still living in Edinburgh in 1833 and had moved to 6 South St David Street. However, it is not currently known where he was laid to rest after his death.

We can only speculate as to the effect his story had on the young Darwin. His accounts of South America must certainly have been inspiring to Darwin. Did Edmonstone help form Darwin’s abolitionist viewpoint? We know from his journals from the Beagle that Darwin noticed cruel acts during the voyage which he found repugnant.

In 2009, a plaque was unveiled in his memory on Lothian Street, although it has since disappeared. But awareness of Edmonstone has grown in recent years and we can hope that his story, and that of other Black people contributing to the study of natural history, continues to be told.

Explore the collections

From giant fossil mammals to mysterious moths, uncover the colourful stories behind some of our most fascinating specimens.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media