Ida Slater was one of the first women palaeontologists in London. She made significant contributions to the male dominated world of geology, paving the way for future women scientists.

Ida Slater was born during the Victorian era and made important contributions to geology

Who was Ida Slater?

Ida Lilian Slater (1881-1969) was born into a wealthy family in Hampstead, London in 1881. She was one of four children of Mary Emily Wilkins (1846-unknown) and John Slater (1847-1924), a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (FRIBA).

Slater went to the all-girls South Hampstead High School. A good education and a thirst for knowledge motivated her to then study geology at the Newnham College in Cambridge, where she joined the Sedgwick Club and became its honorary secretary. Prior to becoming a geologist, Slater also explored geomorphology and stratigraphy.

Slater challenged the patriarchal system of the Victorian era in many ways. Although women were allowed to study, they were not allowed to graduate from most universities, including Cambridge. So she travelled solo to Dublin to gain her first class degree.

It was uncommon for a woman to travel unaccompanied during that time; however Slater's love of learning and discovery kept her driven. She continued to defy the norm by taking further trips abroad to visit colleagues and do fieldwork.

Slater went on to make great strides in the field of palaeontology, especially in the study of conulariids, a poorly understood group of fossils.

Dr Consuelo Sendino, an invertebrate’s curator at the Museum, says, 'Slater made important contributions to our understanding and knowledge of the Early Palaeozoic, and of course the taxonomy of conulariids.'

Slater's conulariid collection resides in the Museum. Consuelo believes it is the best in the world in terms of diversity, and second-best in its number of specimens.

Consuelo says, 'Her work has been cited for over one hundred years and continues to be cited to this day by researchers on this group of fossils.'

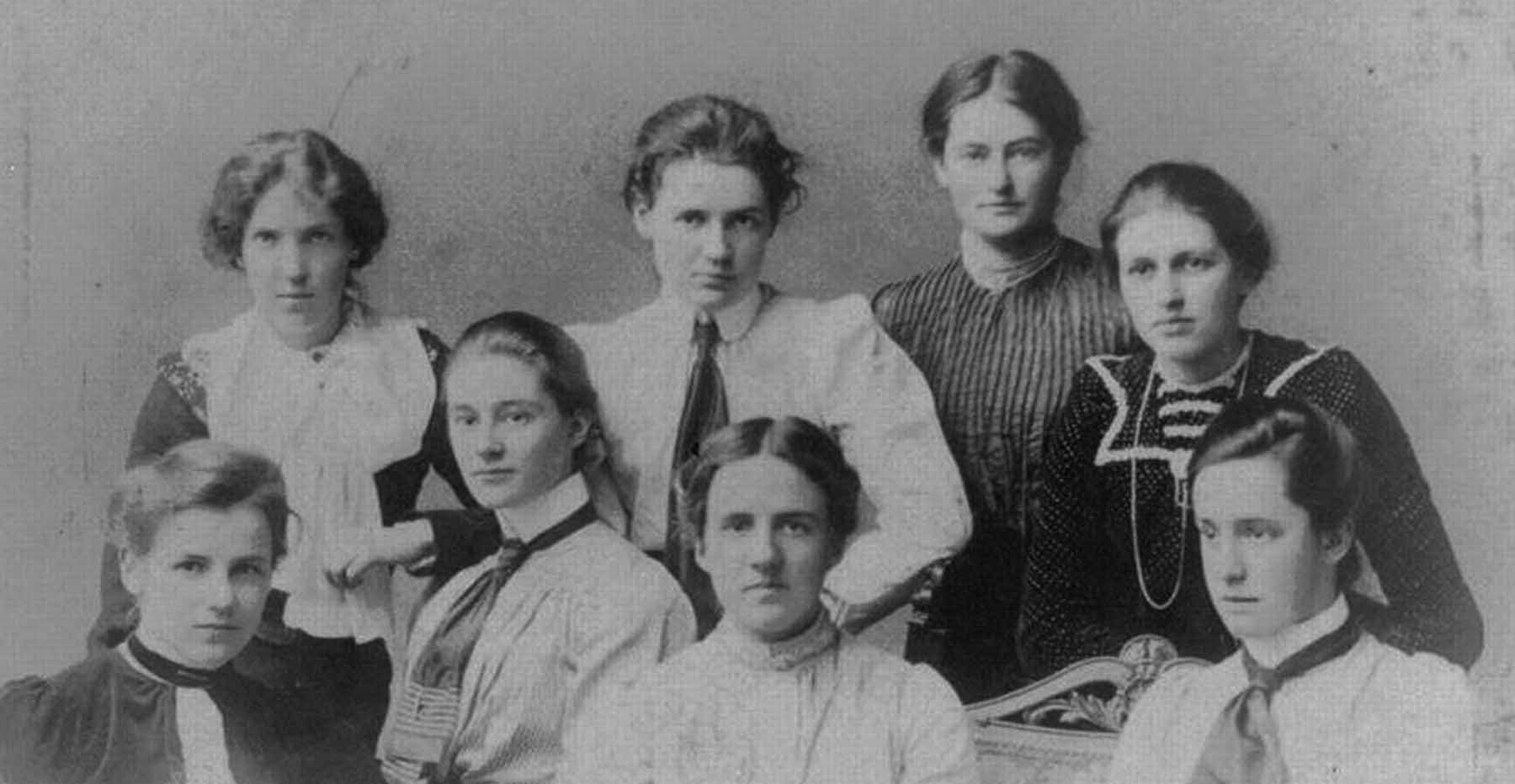

First-year students at Newnham College (1900), with Ida Slater sitting at the front row, far right © The Geological Society of London 2007

Pioneering in palaeontology

Ida's earlier work focused on geology, as evidenced in her first paper, On the Probable Origin of Some Types of Valleys. In it, she explored the origin of U- and V-shaped valleys, concluding that the U-shaped ones were not always originated by ice action. The theory had never been considered nor researched, and was even disputed by other established male geologists.

Slater stood her ground, though it was not until the end of the twentieth century that her theory was proven right. The paper was not published, though the summary can be seen in the notes she took as honorary secretary of the Sedgwick Club.

It was Henry Woods, Slater's palaeontology lecturer in Cambridge, who acknowledged her passion and encouraged her to study conulariids. Conulariids were once a type of jellyfish polyp stage and then a group a fossils which had never been studied in Britain.

Collecting fossils was generally overlooked by men as it was considered a pastime for middle-class women. This disregard gave women a chance to demonstrate their genuine interest in science and leave a legacy for future generations. Slater was good at spotting opportunities and saw this as a way of making her mark.

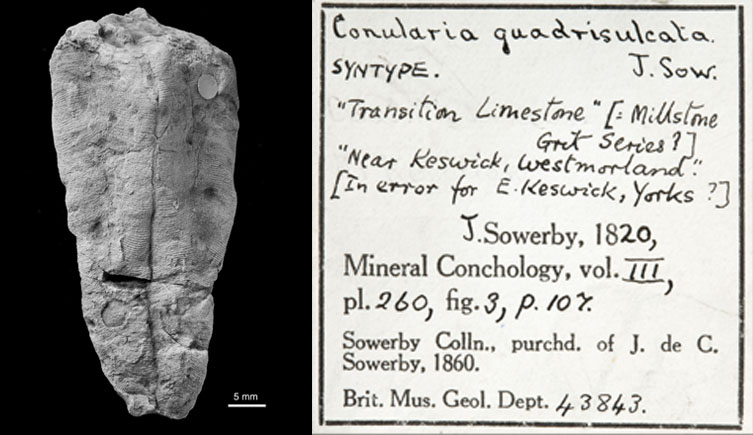

A specimen of Conularia quadrisulcata, described by Sowerby in 1821, available at the Museum

To carry out her research, she frequented the British Museum, where she met and became friends with Dr Arthur Smith Woodward, a former keeper of the Geological Department.

Woodward was impressed with Slater's knowledge and commitment, and asked her to prepare a monograph of the British conulariids for the Palaeontographical Society, which was later completed and published in 1907.

During her research, Slater travelled abroad to compare the Museum's specimens to those of other institutions and private collectors, a procedure which is still followed today.

She applied for funding - another exceptional act for a Victorian woman - with the support of Woodward, and was awarded the Daniel Pidgeon Fund from the Geological Society to investigate Palaeozoic rocks of Wales. Slater's ambition to make a difference was starting to come true.

Besides palaeontology, geomorphology and stratigraphy, Slater was very good at illustrating. She secured work as an illustrator and also created a series of drawings celebrating the signing of the Entente Cordiale of 1904, marked the end of nearly a thousand years of conflict between Britain and France.

Her illustrations were exhibited at the Franco-British Exhibition in London in 1908, a public fair that attracted over eight million people. This provided her with much-needed income.

Slater's last year of proper work was during 1911 where she worked part time as a demonstrator for another trailblazing woman geologist, Catherine Raisin . She spent the rest of her time collaborating with Gertrude Lilian Elles and Ethel M R Wood on their monograph on graptolite plates.

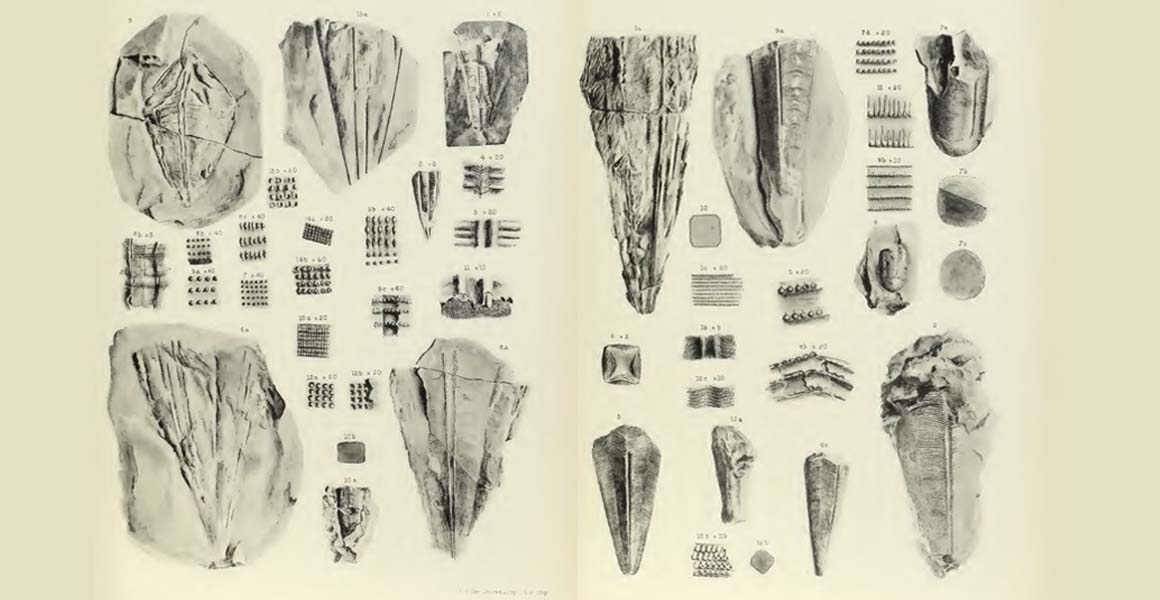

Drawings by Slater from Slater's monograph

Ida Slater's legacy

Slater ceased working completely after marrying a Kensington solicitor in 1912.

Despite her short scientific career, Slater made an impact in more ways than one. She was one of the few women to carve a place in a world of geological research dominated by men, seek and gain funding opportunities, travel solo around Europe and finally became a demonstrator at an all-female college, inspiring the next generation of female geologists. She also wrote three papers, one monograph and drew plates for publications and exhibitions professionally.

While Slater is known for her work in palaeontology, her success expands beyond that. She was, and still is, an epitome of female empowerment, displaying many traits needed to achieve a dream. In a world where women were presented with nothing but obstacles for wanting the same opportunities as men, Slater exhibited bravery, resilience, passion, determination and intelligence.

Her actions and achievements suggest she was ahead of her time, changing not only how women were perceived in the professional environment but also inspiring other women to accomplish the same.

As women were rarely credited for their input during that period, she may have achieved even more, which went unnoticed.

However, one thing is for sure. Ida Lilian Slater indeed left her mark on the world in more ways than one.

Read more

- Find out what Dr Sendino is currently working on.

- Learn more about the Victorian era.

- Who was Catherine Raisin?

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media