A beetle rolling a big ball of poop is as fascinating as it is funny.

A dung beetle transporting its food in the Kruger region of South Africa © Henk Bogaard/ Shutterstock

Do you know why dung beetles roll balls of poo, or how they find their way?

Discover all you need to know about these fascinating insects.

What is a dung beetle?

Dung beetles get their name from their diet of animal poo. Wherever there are herbivorous mammals leaving droppings, there are beetles making the most of it.

But scientific discoveries show there's more to the insects than what they eat.

All dung beetles belong to the scarab superfamily (Scarabaeoidea). But not all scarab beetles eat dung. Those that do include the earth-boring dung beetles (Geotrupidae), the true dung beetles (Scarabaeinae) and small dung beetles (Aphodiinae).

Dung beetles have been around since the time of the dinosaurs. They then flourished as mammals and their droppings increased. These insects are now found on every continent, except Antarctica.

How big is a dung beetle?

'The smallest species are only two millimetres long. Some live in the nests of ants and some small species cling to the fur of sloths or monkeys waiting for fresh substrate to appear,' says Max Barclay, Senior Curator of Coleoptera at the Museum.

'The largest may be the elephant dung beetles of the genus Heliocopris, different species of which are found in Africa and Asia and can reach 70 millimetres. As the name suggests, these feed in the dung of very large animals.'

You can see an exhibit named The Swarm in Hintze Hall. It features hundreds of preserved African dung beetles in flight.

Max explains that there are about 5,750 species of dung beetles in the Coleoptera collection. Scientists have recorded around 9,500 species in total.

'In the last 10 years the collection has increased by about 500 newly added or newly named species,' says Max, who has collected dung beetles all over the world.

'The most recently named was a new species of giant dung beetle from India and Sri Lanka called Heliocopris ares, discovered from old specimens in the Museum collection, and named by two collaborators Philippe Moretto and Robert Minetti in 2022. It was named after Ares the Greek God of War because of its very large horns.'

Myths and legends

The Ancient Egyptians revered several species, particularly the sacred scarab, Scarabaeus sacer.

These scarab beetles feature in religious and funerary art from statues to jewellery. They are said to represent Khepri, the god of the rising Sun.

Philosophers link the images of scarabs and balls to Ancient Egyptian beliefs surrounding resurrection, as Khepri rolls the Sun across the sky each day, through the 'other world' at night and begins afresh in the morning.

A sacred scarab statue at Karnak temple in Luxor, Egypt © Sergii Figurnyi/ Shutterstock

Only a minority of the world's dung beetles are these iconic 'rollers'. There are also 'tunnellers' which bury the dung where they find it. A third approach is to move into a pat or pile of poo to become 'dwellers'.

In the UK, we have more than 60 species of dung beetle. Most are dwellers but some of the largest ones are tunnellers.

One of the UK's most striking dung beetles is the minotaur beetle, Typhaeus typhoeus. It gets its name from the three 'horns' males have to defend territory and compete for females. Found in heath and moors, they are widespread but scarce.

You may be more likely to hear the dor beetle than see it © Martin Fowler/ Shutterstock

A more familiar sighting is the dor beetle, Geotrupes stercorarius. It measures up to 25 millimetres, has a distinctive blue sheen and favours horse manure and cow pats. The dor beetle is most active in lower light. You may hear the hum of its wings on late spring evenings as it searches for suitable poop.

Most dung beetle species have wings and use them to fly between droppings. They're concealed beneath tough wing cases known as elytra.

The flightless dung beetle of South Africa, Circellium bacchus, is a wingless species. It may have shed its wings as an evolutionary adaptation so it can conserve water.

Dung beetles use their wings to travel between food sources © IanRedding/ Shutterstock

What do dung beetles eat?

Dung beetles consume poo throughout their life cycle. Adults' antennae give them a superb sense of smell to find fresh faeces. They either move into this or collect it in underground chambers.

After mating, females lay their eggs on the poo. Some lay theirs inside a 'brood ball' made of poo bound together with saliva. Dung beetle larvae have sharp mouthparts. They use these to chomp through coarse droppings. The adults also slurp nutritious liquid from the leavings.

Eating poo is known as coprophagy. It might sound gross to us but it allows the beetles to access important nutrients that have passed through the guts of mammals. One scientific study identified that dung beetles are actually picky eaters. The beetles target the nitrogen rich particles in droppings. This helps them to build proteins, including muscle.

Most species target the poo of herbivores and omnivores. Some eat fungi, fruits and rotten plant material and other dung beetles are predators. Deltochilum valgum in Peru hunts millipedes, and Canthon virens in Brazil eats the queens of leaf-cutter ants.

Dung beetle larvae start life with plenty of provisions © Henrik Larsson/ Shutterstock

Beneficial beetles

Dung beetles play an invaluable role in ecosystems. It's fair to say that without them, we could be up to our knees in poop.

'Dung beetles are very effective at clearing up waste products,' says Max.

'When the first Europeans went to Australia and brought sheep and cattle, they didn't bring any dung beetles. So, they had a problem with the dung not being cleared away and they were plagued by flying insects. The flies had a bonanza because there was so much dung and no dung beetles.'

An inventive hat strung with corks to keep flies away became a national symbol of Australia. In the 1960s, the government spent millions of dollars to introduce dung beetles. Hats off to the decomposers!

Dung beetles improve pasture by removing waste and keep fly populations under control. By burying poop they also improve soil conditions and return nutrients through their own excretions. Researchers suggest that protecting UK dung beetle species could save the cattle industry more than £40 million a year.

How strong is a dung beetle?

As well as recognition as a clean-up crew, we must celebrate dung beetle strength.

The Florida deepdigger, Peltotrupes profundus, only measures up to 23 millimetres. This tiny beetle has been recorded tunnelling three metres underground and pushing out all the soil.

The taurus scarab, Onthophagus taurus, needs powerful muscles to defend its territory. Females dig mating burrows to attract a mate and males must push their rivals out of the tunnel. The strongest males can pull 1,141 times their own body weight, the same as a person pulling six double decker buses! This makes these dung beetles the strongest animals on Earth for their size.

'Rollers' regularly transport balls of poo that are 10 to 30 times their size. In extreme cases some can roll balls 79 times their own body weight. They can travel up to 200 metres to find a safe place to bury what they find.

It's not greed motivating this behaviour but scarcity. Dung is relatively rare and there's a lot of competition for it.

A flightless dung beetle rolling elephant dung with its powerful back legs © Michael Sheehan/ Shutterstock

How do dung beetles navigate?

Under pressure from rivals, predators, and extreme heat, dung beetles that roll poo need to travel efficiently. Researchers in South Africa have discovered amazing celestial connections that would delight the Ancient Egyptian scarab superfans.

Scarabaeus lamarcki has been found to use the Sun and light levels as a compass to help it travel in a straight line.

For night-active species, the Moon is a less reliable source of light as it changes through the month. But researchers found that Scarabaeus zambesianus uses the way moonlight scatters through the atmosphere to orientate itself. When presented with non-polarised light in a test arena, the insects travelled in circles.

Scarabaeus satyrus uses the Milky Way to navigate on moonless nights. Researchers tested their theories both in the field and at the Johannesburg Planetarium.

Dung beetle discoveries and detectives

Dung beetles have long captured our interest.

Scientists have made many discoveries about their behaviour in recent years. Some species dance on top of dung balls to take a 'celestial snapshot' to help them navigate. Others rest their hot feet on top of dung balls, and some species have puzzled researchers by appearing to gallop.

For Max, some of the most exciting research puts dung beetles in the role of detective.

'One thing that's quite exciting is looking at the DNA from the intestines of dung beetles to see what kind of animals produced the dung they ate,' he explains.

By looking at beetles in the collection, researchers can compare past diets with those now to see how mammal populations have changed. Conservationists can also inspect dung beetle diets to find out if an elusive species of mammal is present in an area. This could limit the need for expensive camera traps.

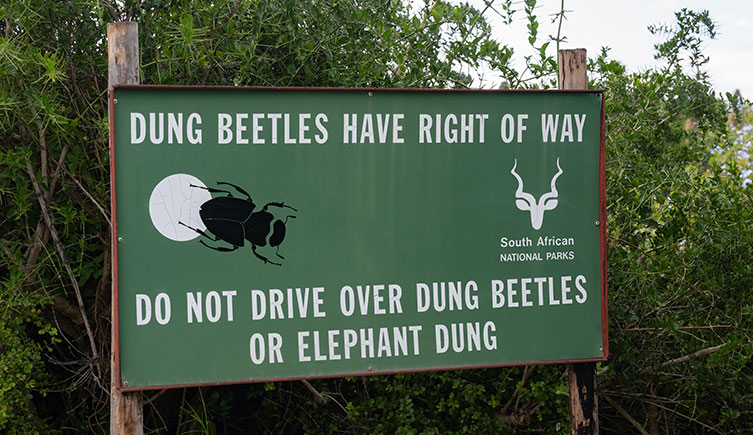

South Africa's Addo Elephant National Park asks drivers to protect dung beetles. © Natascha Kaukorat/ Shutterstock

But for all their amazing adaptations and biological benefits, populations of dung beetles are in decline. Threats include the use of pesticides in intensive farming and worming treatments for livestock that make dung toxic.

It seems the modern world could learn from the ancient one, and we should value all scarabs as sacred.

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Is this stool taken?

Pull up a seat and unlock the survival secrets of dung beetles and their relatives in our online and on-demand course.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media