When the crew of HMS Endeavour arrived to observe the transit of Venus at Otaheite (Tahiti) in 1769 they established a fortified observatory known as Fort Venus

Sydney Parkinson (1773). Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Endeavour 250: natural history through colonial encounter

Kerry Lotzof

In August 1768, under the command of then-Lieutenant James Cook, HMS Endeavour and her crew set sail for Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus - before opening sealed orders for a secret assignment.

The secret mission was to locate and claim the great southern landmass, so-called Terra Australis Incognita ('unknown land of the South'), for the British crown and secure any other territories they found along the way which could be useful to the Empire.

The Endeavour voyage greatly expanded Western scientific knowledge of the South Pacific and foreshadowed British colonisation in the region.

HMS Endeavour and her crew

In 1768 a refitted coal ship known as HM Bark Endeavour left Plymouth for the South Pacific island of Otaheite (Tahiti). Slow-moving and sturdy, the ship had a shallow hull that was ideal for sailing in unknown and potentially treacherous waters.

On board was a full naval complement of 85, including a dozen marines armed with gunpowder, cannons and swivel guns. There were also nine civilians, including the renowned astronomer Charles Green as well as the young naturalist Joseph Banks and his party of four servants, a secretary, two artists, a botanist and two dogs.

The wealthy 25-year-old Banks had persuaded his connections in the Admiralty to allow him on the voyage at the last minute, at his own expense.

The two artists appointed by Banks were Scottish landscape artist Alexander Buchan and Scottish naturalist artist Sydney Parkinson. Banks's secretary Herman Sporing was also an accomplished artist. To assist with collecting and identifying species Banks brought his good friend, the Swedish botanist Daniel Solander.

The success and scale of discovery recorded by Banks's group set a precedent for including artists on future voyages.

The transit of Venus

Officially, the crew of the Endeavour were to sail to Tahiti to chart the transit of Venus, which occurs when a relatively small celestial body (in this case Venus) passes across the disk of a larger body, such as a sun eclipsing a small area. This was a key phenomenon in early astronomy.

Knowledge of the precise times taken for the transit as observed from different point of Earth's surface enabled astronomers to accurately calculate the distance between Earth and the Sun.

Cook worked with the ship's astronomer Charles Green on this task.

Charting the transit of Venus was a vital activity in early astronomy that allowed scientists to measure the distance from Earth to the Sun.

Transit of Venus: Cook and Green. From The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1771. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Unfortunately, cloud cover during the event made it impossible to make reliable observations.

Transit of Venus: Cook and Green. From The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1771. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

A secret mission

Once the celestial observations were made, Cook opened the sealed orders from the Admiralty. Until that moment only he was privy to their contents.

Inside were instructions to search for and lay claim to Terra Australis Incognita, a partially charted landmass assumed to occupy much of the southern part of the globe. The transit of Venus mission was a cover for a journey to claim any promising South Pacific land for Britain ahead of rival European powers.

The plan worked marvellously.

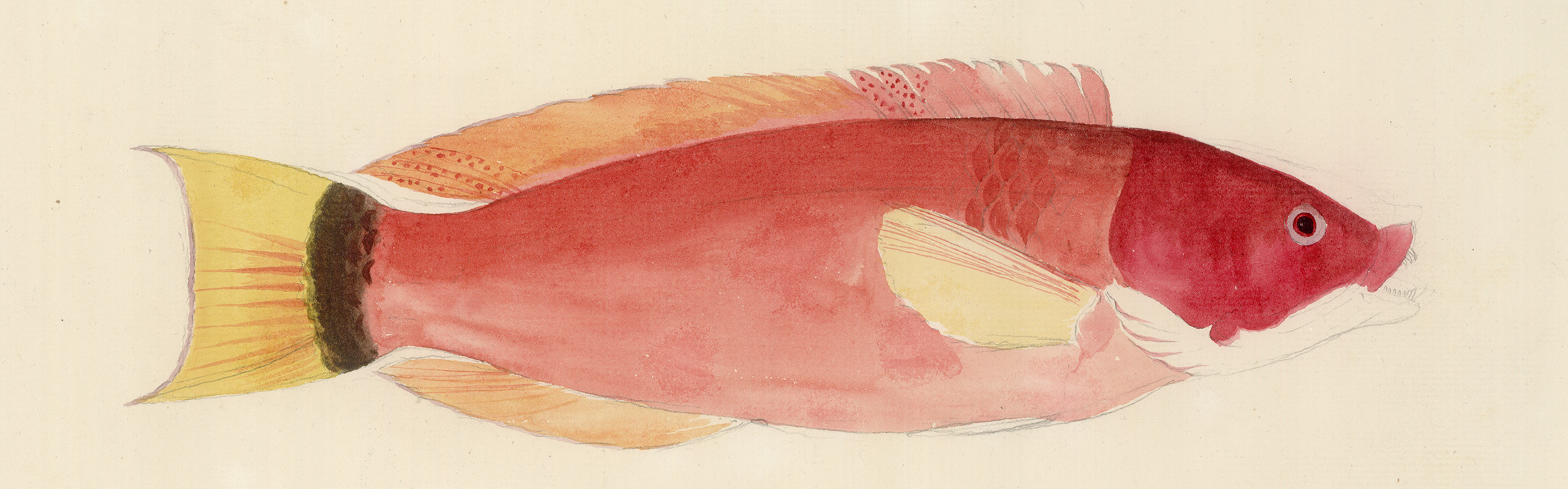

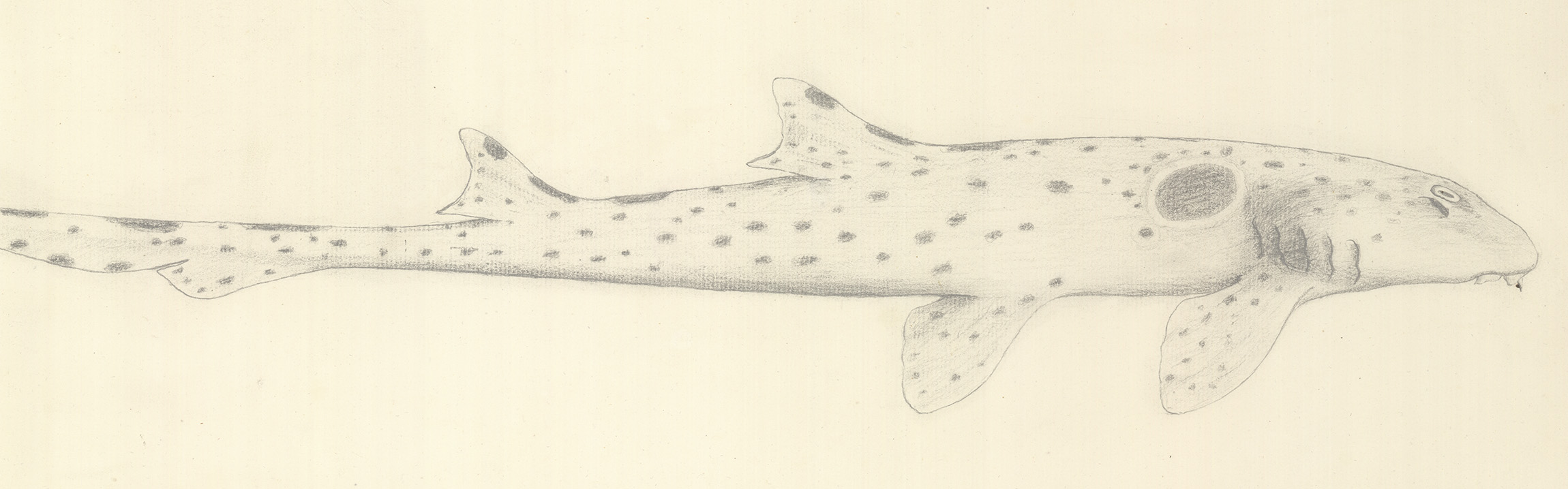

Pencil sketch of an Epaulette shark, or Hemiscyllium ocellatum

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771). Graphite on paper. Source: The Natural History Museum, London

Instructions from the Admiralty read:

'You are [...] to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard; taking Care however not to suffer yourself to be surprised by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents.

'You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.

'You are also to carefully to observe the Nature of the Soil, and the Products thereof; the Beasts and Fowls that inhabit or frequent it, the Fishes that are to be found in the Rivers or upon the Coast and in what Plenty and in Case you find any Mines, Minerals, or valuable Stones you are to bring home Specimens of each, as also such Specimens of the Seeds of the Trees, Fruits and Grains as you may be able to collect, and Transmit them to our Secretary that We may cause proper Examination and Experiments to be made of them.'

Cook's interpretation of these instructions continues to be a subject of important historical and political debate.

The first scientific description of a kangaroo was recorded by Daniel Solander when the Endeavour was forced to make an extended stay on the Endeavour River in Queensland to make repairs after hitting a coral reef. Linguists believe that the 'Kanguru' name which Cook recorded in his diary entry of 4 August 1770 is derived from a word in the Aboriginal language of the Guugu Yimidhirr people, whose word 'gangurru' refers to a species of kangaroo.

Unfinished pencil outline of a 'kanguru' by Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771). Graphite on paper, 1770. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Who discovered Australia

Australia has been continuously inhabited by Aboriginal people for 30,000-70,000 years.

European sailors first entered Australian waters in the early 1600s - they were the ones who called the unknown land mass Terra Australis Incognita. Between 1606 and 1770 more than 50 European ships had made landfall in Australia.

In 1642, Dutchman Abel Tasman mapped Van Dieman's Land, now Tasmania. On a second voyage in 1644 he encountered and charted much of the western and southern coast of present-day Australia, naming it Nova Hollandia (New Holland).

Well over a century later, on 29 April 1770, James Cook and the crew of HM Bark Endeavour landed in Botany Bay, home of the Eora people. Despite this area being populated, Cook declared the east coast of Australia Terra Nullius - 'nobody's land' - and claimed it for Great Britain.

The voyage of the Endeavour

The first stop on the way to Tahiti was Funchal in Madeira Island (off the west coast of Morocco). HMS Endeavour arrived there on 12 September 1768 and paused to take on fresh supplies before crossing the Atlantic.

During this time, Banks and Solander listed 230 plant species, 25 of which were new to Western science.

On 13 November they arrived at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where Cook received an icy reception from the Portuguese viceroy, who refused to allow the Endeavour to anchor in the harbour. Portugal and Great Britain were competing European naval and colonial powers.

Watercolour illustration of a Madeira cockroach Rhyparobia maderae. Cockroaches, lice, rats and maggots carried disease and could wreak havoc on the ship's food supplies. The artist, Alexander Buchan, died as a result of an epileptic seizure only eight months into the voyage.

Alexander Buchan (d 1769) Watercolour on paper, c 1768 -1769. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Despite the restriction put in place by the Viceroy, members of the crew went ashore at night in small boats. Wiñay wayna (Epidendrum secundumI) is an orchid found in montane forests in Central and South America.

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771). Watercolour on paper, 1768. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

The diaries of both Cook and Banks offer a thorough reconnaissance of the region's natural resources and trade, and the harbour's defensive structures.

From Rio, the ship sailed to the Strait of Le Maire (at the southern tip of Argentina) and landed shore parties in Tierra del Fuego before passing the treacherous southernmost point of South America, Cape Horn.

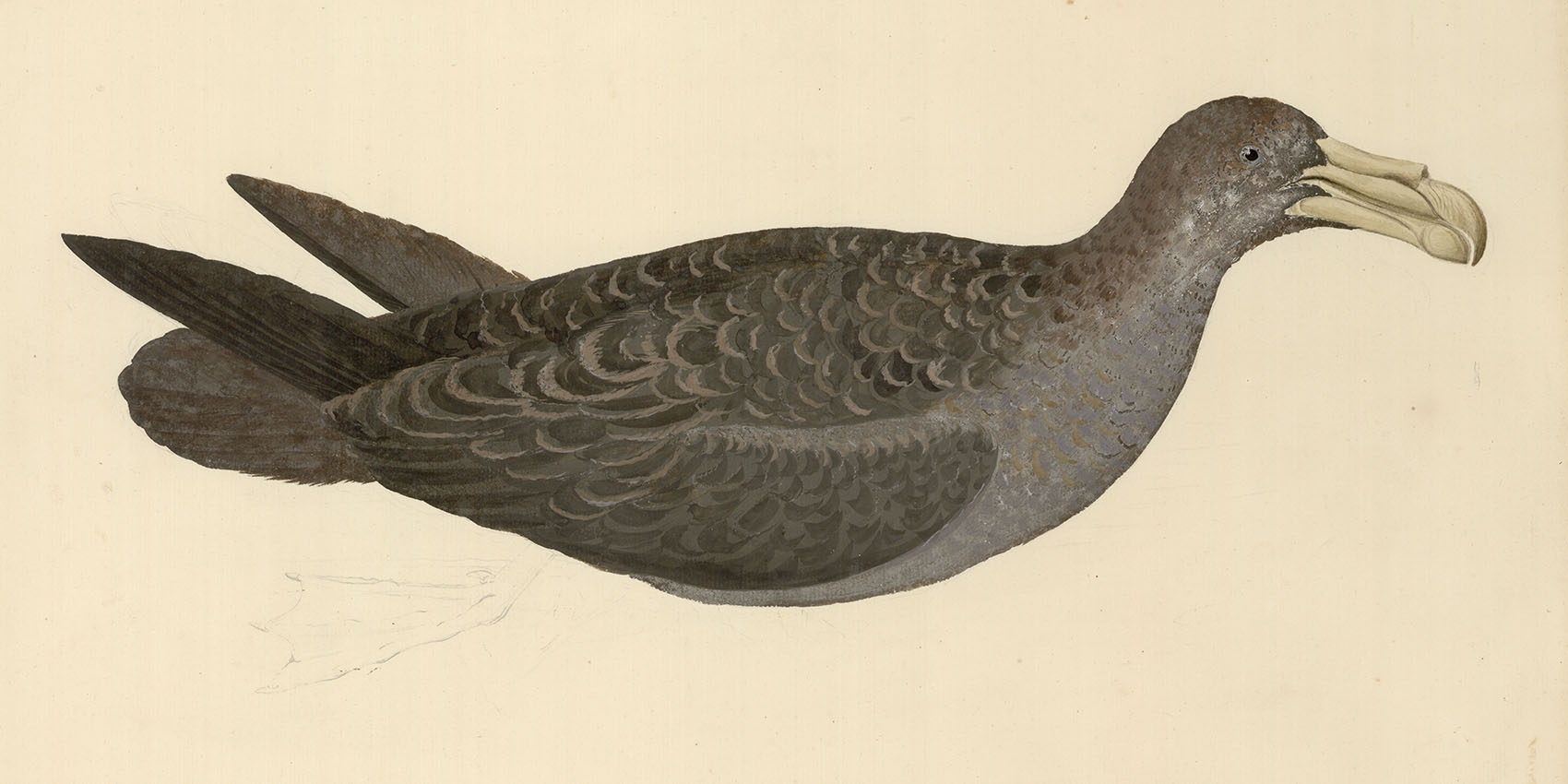

Southern giant petrel Macronectus giganteus. Parkinson undertook this illustration of a southern giant petrel on 23 December 1768 en route to Tierra de Fuego near the southern tip of South America. Parkinson never completed the drawing but added a note saying that 'the feet are grey'.

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771). Watercolour on paper, 1768. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Tahiti, April-July 1769

The Endeavour entered the Pacific in late January 1769 and arrived on 13 April at Matavai Bay, Tahiti, seven weeks before the transit of Venus was due to occur. Tahiti had only been plotted on Western maps the year before.

The crew erected fortifications and forged relationships with the inhabitants for the supply of food and local knowledge of the region.

One of the most important relationships was with Tupaia, a Polynesian navigator and Arioi (a Māori spiritual figure), who voluntarily joined the Endeavour voyage in Tahiti.

Cook, Banks and his retinue drew heavily on Tupaia's skills as a navigator, translator and local guide to map the region and identify new species and potentially useful resources.

Unfinished sketch of the foliage and fruit of the breadfruit tree Artocarpus altilis. Specimens and sketches were also taken of the sweet potato (Tahiti) and taro (Australia).

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771). Graphite on paper, c 1769. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Finished watercolour of the foliage and fruit of the breadfruit tree Artocarpus altilis. Joseph Banks recognised the potential of breadfruit as a cheap food crop to feed enslaved people in other tropical areas. He proposed to King George III that a special expedition be commissioned to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the Caribbean. For this, William Bligh took command of the notorious HMS Bounty in 1787.

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771). Watercolour on paper, 1769. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

The search for the southern land, July-October 1769

Working with incomplete maps created by the explorer Abel Tasman more than 100 years before, in mid-July 1769 Endeavour sailed south in search of Terra Australis Incognita.

The course was far from smooth. With no preset destination, the exploratory voyage zigzagged around the area - according to a map pencilled in Cook's own hand, it even made at least two complete loops. From the Society Islands they travelled south, then north-east, then north-west and east again.

Having still encountered no major land mass, the crew turned south-west again and encountered the eastern coast of New Zealand on 7 October.

Sydney Parkinson was fascinated by the people he encountered during the voyage. His journals document many cultural aspects of Indigenous People, including languages and customs. He was particularly interested in the Māori warriors he encountered and their method of tattooing.

Engraved plate from A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas in His Majesty's Ship the Endeavour [1768-1871] … by Sydney Parkinson (1773). Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Head of Otegoongoon, son of a New Zealand Chief, with details of his tattoos

Engraved plate from A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas in His Majesty's Ship the Endeavour [1768-1871] … by Sydney Parkinson (1773) Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

New Zealand, October 1769 - March 1770

Cook took a very thorough approach to charting New Zealand, sailing anti-clockwise around the North Island then through Cook Straight and then clockwise around the South Island.

The crew also made several short land excursions along the way, many of which did not go according to plan.

Parkinson died six months before Endeavour returned to England, so Banks employed a team of artists, including Frederick Nodder, to complete watercolours of Parkinson's unfinished sketches. Nodder completed this watercolour of New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) based on sketches by Parkinson and the specimens collected by Banks and Solander. New Zealand flax, known to Māori as harakeke, was used to create clothing, rope and tools.

Frederick Nodder (fl 1770 - c 1800). Watercolour on paper, 1783. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

Herbarium sheet of puriri (Vitex lucens) collected by Banks and Solander. Puriri is an evergreen tree endemic to New Zealand and provides some of the strongest wood available in the country. Puriri trees or groves were sometimes considered tapu (taboo) due to their link with Māori burial customs. European settlers used great quantities of the timbers for fence posts, house and ship building.

Source: The Natural History Museum, London

Within half a day of Cook landing in New Zealand, the first Māori had been shot. Many more deaths by musket fire followed.

Deaths and misunderstandings continued until Cook forcefully acquired two young hostages and plied them with gifts of beads, ribbons and nails in order to establish the crews friendly intentions. At this time Tupaia's invaluable role as translator really came to the fore and Cook was able to establish a wary alliance with the locals.

Taking hostages would become Cook's go-to diplomatic method in the region. This was an effective tactic for Cook until his third visit to Hawaii in 1779 when Indigenous warriors retaliated during the attempted abduction of their chief, leading to Cook's death.

This watercolour on paper, is attributed to Tupaia and depicts a Maori and Joseph Banks trading a crayfish for a piece of cloth

Tupaia, 1769 © British Library, Add MS 15508, f. 12

This pygmy slipper lobster Biarctus sordidus was collected by Joseph Banks while on board the Endeavour

Source: The Natural History Museum, London

HMS Endeavour departed New Zealand on 31 March 1770 and was subsequently remembered by Māori as 'Tupaia's ship'. The British Library has compiled responses to the arrival of the Endeavour from across the Pacific.

East coast of Australia, April-October 1770

The Endeavour headed west again, bound for the uncharted eastern coast of Australia to pick up where Abel Tasman had left off more than a century earlier.

After weeks at sea, the ship finally arrived at the southeast tip of the continent on 19 April 1770, having sailed north for more than 3,200 kilometres (2,000 miles) along the east coast of Australia.

During the trip, many fruitful land excursions were made, one of the best known being in present-day Sydney, then called Botany Bay - so-named for the abundance of new plants collected there.

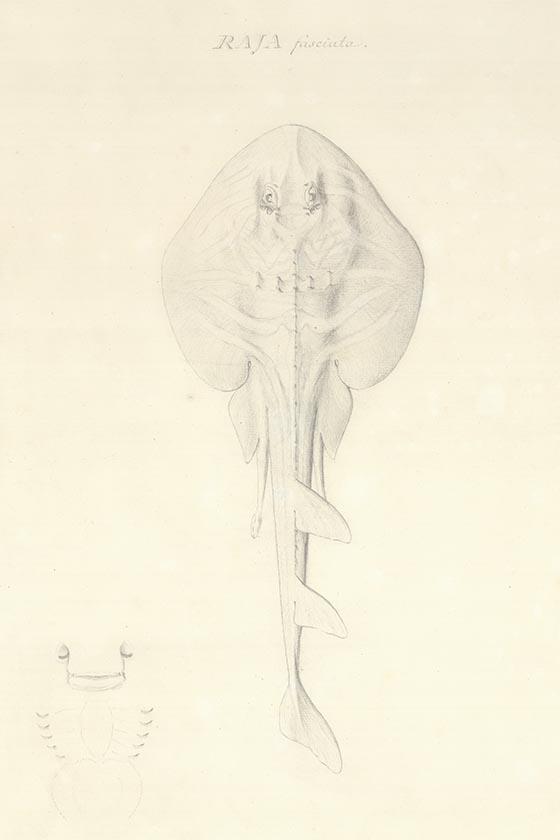

Trygonorrhina fasciata. According to Cook's journal, the first name given to the region that would be named Botany Bay was Stingrays Harbour, after the quantity of rays they encountered there. It was later renamed Botany Bay for the many plants found there by Banks and Solander.

Herman D Sporing (1733-1771). Watercolour on paper, c 1770. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

This undecorated Gweagal shield, made of long-style stilt mangrove (Rhizophora stylosa) with a pierced hole near the centre, may have been obtained by Captain Cook on 29 April 1770 at Botany Bay. In his journal, Cook writes: 'Defensive weapons we saw only in Sting-Rays [Botany] bay and there only a single instance - a man who attempted to oppose our Landing came down to the Beach with a shield made of the bark of a tree; this he left behind when he ran away and we found upon taking it up that it plainly had been pierced through with a single pointed lance near the centre.' The shield has become a symbol of Aboriginal resistance to European settlement. The Australian Museum has more information on the origins of this shield.

Made by an unknown aboriginal Australian © CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 The Trustees of the British Museum

Banks and Solander collected new material there almost every day, and Parkinson drew more than 400 sketches of plants while the ship was in Australian waters.

Thanks to Banks and Solander's prolific botanical collecting, Parkinson made detailed outline sketches with colour references of each plant, for later completion.

The original herbarium sheet for Tropica banksia collected by Daniel Solander. Eminent taxonomist Carl Linnaeus was so impressed with the scale of discoveries made by Banks and his party that he proposed that New South Wales should be named Banksia in his honour. Instead, the name Banksia was given to genera and species of plants.

Source: The Natural History Museum, London

Old man banksia, or Banksia serrata. Parkinson included the note 'Mem. the space below the flowers to be fill'd up wt dark colour' on his outline drawing of this plant which he undertook in Botany Bay. The finished watercolour was completed by John Frederick Miller following the Endeavour's return to England.

John Frederick Miller (1759-1796). Watercolour on paper, 1773. Source: The Natural History Museum, London.

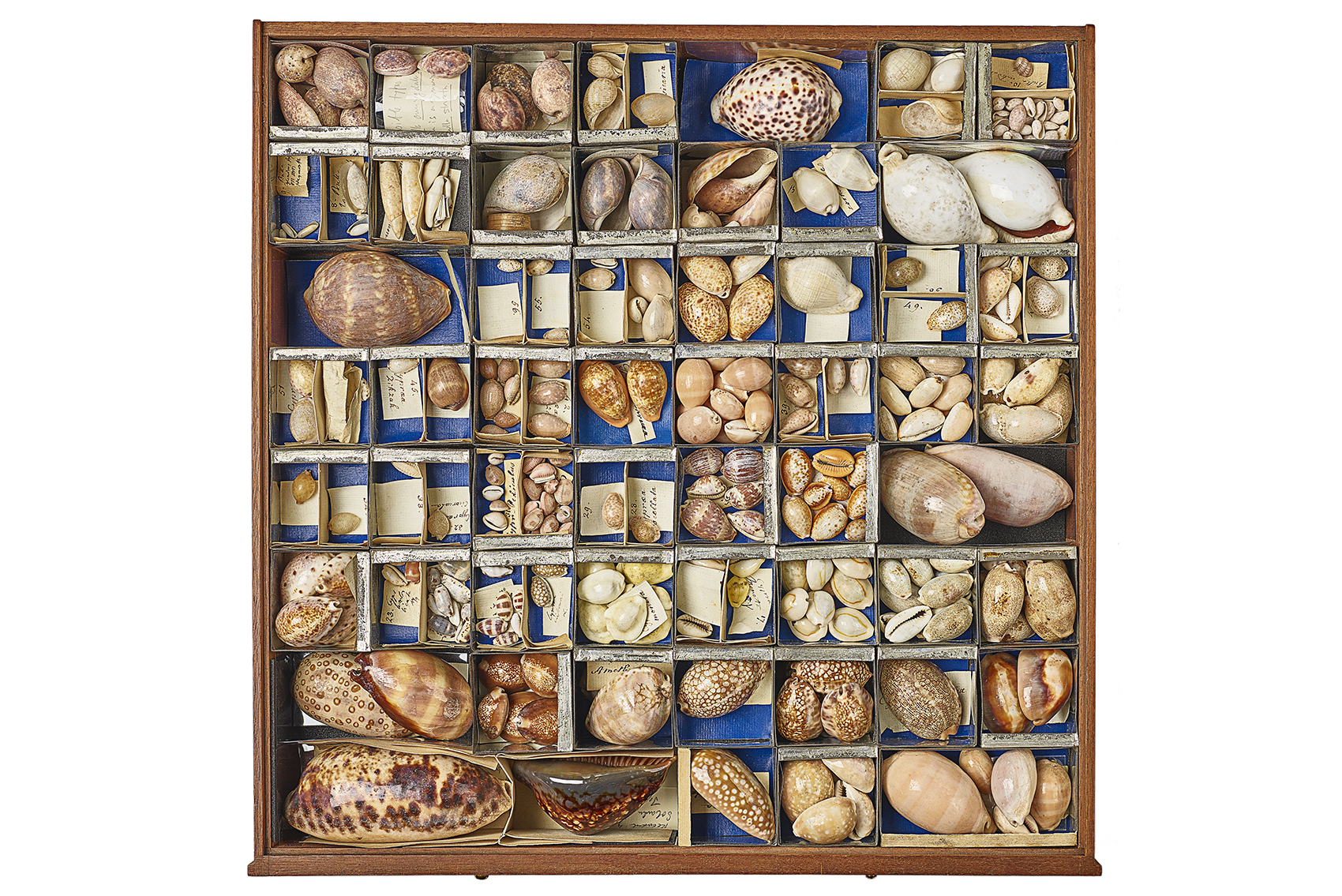

Once strewn across the beaches of Brazil, Tahiti, New Zealand and Australia, these shells are among those collected by Banks during the HMS Endeavour expedition (1768–1771).

Sir Joseph Banks' shells, drawer 6, cowrie collection. Source: The Natural History Museum, London

Cook and his crew met few Aboriginal people on Australia's eastern shoreline, but were fully aware of their presence when they claimed the eastern coast for Britain.

Journals entries from those on board the Endeavour mention Aboriginal people lighting warning fires along the coast to alert other communities of the approaching danger.

Loss and legacy

HMS Endeavour arrived at the English port of Dover on 12 July 1771. The crew had been sworn to secrecy about all they had seen.

On the last leg home, from Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), thirty crew members including Sydney Parkinson and Charles Green died of ship-borne illnesses including fever, dysentery and malaria.

Cook received high praise from the Admiralty for the many achievements of the voyage and was promoted to the position of commander.

The resulting natural history collection included more than 1,000 species of plant previously unknown in Europe. Banks, Solander and their colleagues became the toast of the London scientific community.

This early picture of Sydney Cove through European eyes shows Aboriginal inhabitants in the foreground, set against a backdrop of the early penal colony. It is part of a series by early Australian illustrator Thomas Watling, a convict sent to Australia for art forgery with the first fleet.

Thomas Watling, 1792-1797. Source: The Natural History Museum, London

Joseph Banks became one of the most influential scientists of his day, and was appointed as King George III's advisor for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, sending botanists around the world to collect plants on his behalf.

Banks was also highly influential in the decision to establish a British penal colony at Botany Bay in New South Wales. He was made a baronet in 1781 and a Knight Commander of Bath in 1795 for his patronage of natural science.

After his death in 1820, the priceless collection of illustrations and specimens from the Endeavour voyage were left to the Natural History Museum - then the British Museum (Natural History) - where they continue to be cared for today.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media