Delve into the dark world of parasitic wasps and discover their grisly takeovers of living caterpillars.

Wasp larvae emerge from inside a caterpillar © Jeff-o-matic, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Becoming a butterfly is a dangerous game, and it's easy for caterpillars to fall victim to some very unsavoury characters along the way.

As well as facing threats from hungry birds and insects, caterpillars can be devoured by parasitoids, chewed from the inside out.

Dr Gavin Broad, Senior Curator of Hymenoptera, explains the gruesome phenomenon.

A chrysalis invaded

The inside of a chrysalis: dark, sleepy, undisturbed. Or so you would think.

In reality, it's a hiding place that is vulnerable to attack.

Wasps prey on caterpillars and butterfly eggs, using their nutrients before killing them © Katoosha/Shutterstock.com

A butterfly is just one of the creatures that might end up emerging from a chrysalis or a pupa.

Butterflies and caterpillars frequently host parasitoids, insects that attack and destroy their hosts, sometimes eating them alive. These are usually wasps, laying their own eggs inside an egg, caterpillar or pupa.

Parasitoids start their lives as parasites, in or on the body of a host, but they end up as predators, eating the host entirely.

Broad says, 'Butterfly enthusiasts are often disappointed when a caterpillar becomes a pupa but a wasp chews its way out.

'For some of us, though, this is the starting point of an exploration of the amazing interactions between the two.

'As far as we know, parasitoid wasps and flies don't attack adult butterflies - they don't generally live very long, so they're not a good food source.

'But every other stage - egg, caterpillar and pupa - can be attacked, as is the case with most insects.'

A dark ending

A butterfly egg is tiny, but wasps can still develop inside it.

When a wasp larva finds itself nestled inside a butterfly egg, it has all the sustenance it needs in that hard-shelled, protective host environment.

One wasp, Hyposoter horticola, employs a sinister tactic to get inside its host, the egg of the Glanville Fritillary butterfly.

After keeping a close eye on a set of new butterfly eggs, a female wasp will lay its own inside them just before the tiny caterpillar is about to hatch.

Wasp larvae spin their own tough cocoons after breaking free from inside the caterpillar's body © Simon Shim/Shutterstock.com

Broad explains, 'The wasp larva sits tight inside the body of its host until the caterpillar is almost fully grown.

'At that point, the wasp puts on a growth spurt. It eats the entire contents of the caterpillar's body and spins its own tough cocoon to pupate in, before emerging as another adult wasp.'

A bodily invasion

Other species wait until the caterpillar has hatched from its egg to invade.

The tiny larva lurks inside the flesh of the caterpillar, soaking up its host's nutrients and drinking its blood. The wasp larva must keep its host alive, so it avoids damaging the vital organs.

The caterpillar swells as it eats, not knowing what lies ahead.

When the larva is ready to break out, it releases chemicals that paralyse the caterpillar. With its host stuck, the larva uses specialised, saw-like teeth to eat its way through the thick skin.

Remarkably, the wounded caterpillar does not always die. Some species even watch over the newly free larvae until they spin their own cocoons, ready to become adult wasps.

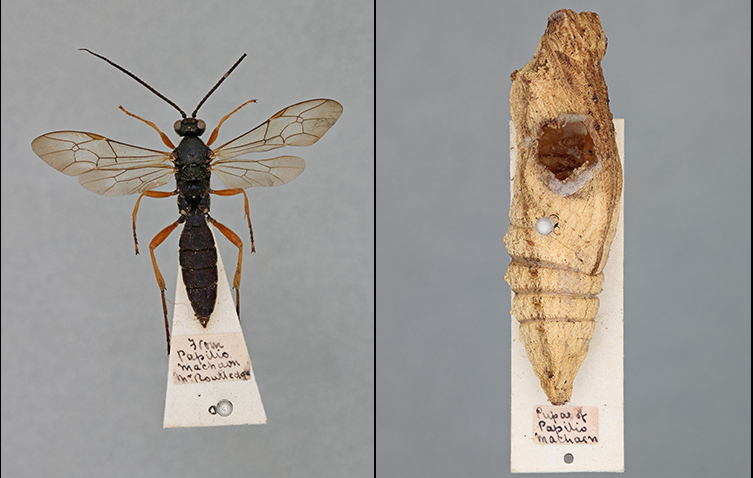

A wasp (Trogus lapidator) specimen in the Museum collection and the pupa it emerged from.

One body, multiple parasites

Some wasps can use hosts that are a lot larger than they are, laying an entire batch of eggs inside the body of one caterpillar.

A species of wasp called Cotesia glomerata does this inside the bodies of large white caterpillars. The large white eats cabbage, making it a common sight in British gardens.

Broad says, 'If your cabbages are being ravaged by butterflies, you might take some comfort from the fact that up to 70 per cent of the caterpillars can be parasitised.

'Some wasps take this to the extreme and just lay one egg that then divides into many identical embryos, a process called polyembryony. Thus a whole mass of wasps can emerge from a host when only one egg was laid in it.'

Museum research

Parasitic wasps are common in Britain - there are at least 6,000 known species.

They can have a huge impact on the population numbers of other insects.

A wasp (Trogus lapidator) emerging from a pupa after devouring the caterpillar inside © Mark Shaw, Pieter Kan, Brigitte Kan-van Limburg Stirum, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Museum scientists are studying the diversity of these wasps, researching what we can learn from them for use in pest control. Experts are also examining why there so many species, and describing any new ones that they discover.

For example, a study was done on Trogus lapidator, a wasp that preys on swallowtail butterflies in the Norfolk fens.

The above image shows a pupa of a swallowtail butterfly. The beautiful butterfly failed to emerge, and the wasp cut a neat circular hole through what would have been the wing pad of the pupa.

Broad says, 'Thankfully, some of these wasps are in our collection.

'It helps us reconstruct a history of the species, Trogus lapidator, in Britain.'

The host butterfly became rare when the fens were drained. But its specialised parasitoid wasp clung on and can still be found in the fens, in much lower numbers than its host.

Broad adds, 'Parasitoids may be gruesome, but they are important and vulnerable to extinction if their hosts are in short supply.

'They play vital roles in structuring the insect communities around us - and some of us find it an awful lot more interesting when a wasp emerges from a pupa, rather than a butterfly.'

We hope you enjoyed this article…

... or that it helped you learn something new. Now we're wondering if you can help us.

Every year, more people are reading our articles to learn about the challenges facing the natural world. Our future depends on nature, but we are not doing enough to protect our life support system.

British wildlife is under threat. The animals and plants that make our island unique are facing a fight to survive. Hedgehog habitats are disappearing, porpoises are choking on plastic and ancient woodlands are being paved over.

But if we don't look after nature, nature can't look after us. We must act on scientific evidence, we must act together, and we must act now.

Despite the mounting pressures, hope is not lost. Museum scientists are working hard to understand and fight against the threats facing British wildlife.

For many, the Museum is a place that inspires learning, gives purpose and provides hope. People tell us they 'still get shivers walking through the front door', and thank us for inspiring the next generation of scientists.

To reverse the damage we've done and protect the future, we need the knowledge that comes from scientific discovery. Understanding and protecting life on our planet is the greatest scientific challenge of our age. And you can help.

We are a charity and we rely on your support. No matter the size, every gift to the Museum is critical to our 300 scientists' work in understanding and protecting the natural world.

From as little as £2, you can help us to find new ways to protect nature. Thank you.

British wildlife

Find out about the plants and animals that make the UK home.

What on Earth?

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Ever wondered if an isopod could eat strawberries?

We haven’t either. But you could find out in one of our new online courses, designed for all levels of interest in the natural world.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media